MuseLetter #351 / May 2022 by Richard Heinberg

Download printable PDF version

Dear reader,

This month’s MuseLetter consists of two essays. The first, “Can We Abandon Pollutive Fossil Fuels and Avoid an Energy Crisis,” maps the constraints of climate/energy policy that will shape the remainder of our lives. The second, “The Energy and Food Crisis Is Far Worse than Most Americans Realize,” is more urgent, and explores the economic and humanitarian calamity now unfolding around us, day by day. I’d also like to call your attention to excerpts from my recent book Power: Limits and Prospects for Human Survival, being published monthly at Resilience.org (we’re up to chapter 3).

With best wishes always,

Richard

Can We Abandon Pollutive Fossil Fuels and Avoid an Energy Crisis?

Similar to the two navigational hazards mythologized as sea monsters in ancient Greece—Scylla and Charybdis—which gave rise to sayings such as, “between the devil and the deep blue sea” and “between a rock and a hard place,” modern energy policy has its own Scylla and Charybdis. On the one hand is the requirement to maintain sufficient energy flows to avoid economic peril. On the other hand is the need to avert climate catastrophe resulting from such activities. Policymakers naturally want all the benefits of abundant energy with none of the attendant climate risks. But tough choices can no longer be put off.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the West’s response of imposing sanctions on Russia are forcing a reckoning as far as global energy policy is concerned. The International Energy Agency (IEA) forecasts that the ongoing war and the U.S. sanctions may together reduce Russian oil exports by at least 3 million barrels per day—more than 4 percent of global supplies, which is a huge chunk of the delicately balanced world energy market. Some energy analysts are forecasting that oil prices could spike up to $200 per barrel later this year, exacerbating inflation and triggering a global recession. We’re facing the biggest energy crisis in many decades, with supply chains seizing up and products made from or with oil and gas (notably fertilizers) suddenly becoming scarce and expensive. Scylla, therefore, calls out: “Drill more. Lift sanctions on Venezuela and Iran. Beg Saudi Arabia to increase output.” But if we go that route, we only deepen our dependency on fossil fuels, aggravating the climate monster Charybdis.

The IEA was created in the aftermath of the 1970s oil shocks to inform policymakers in times of energy supply crisis. The agency recently issued a 10-point emergency plan to reduce oil demand and help nations deal with looming shortages owing to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Its advice includes lowering speed limits, instituting car-free Sundays, encouraging working from home, and making public transport cheaper and more widely available.

All of these are good suggestions—and are very similar to what my colleagues and I have been advocating for nearly 20 years (some were even part of U.S. energy policy 50 years ago). Fossil fuel supply problems shouldn’t come as a surprise: we treat these fuels as though they were an inexhaustible birthright; but they are, of course, finite and depleting substances. We have extracted and burned the best of them first, leaving lower-quality and more polluting fuels for later—hence the recent turn toward fracked oil and gas and growing reliance on heavy crude from Venezuela and “tar sands” bitumen from Canada. Meanwhile, rather belatedly, it has gradually dawned on economists that these “unconventional” fuels typically require higher rates of investment and deliver lower profits to the energy industry, unless fuel prices rise to economy-crushing levels.

Indeed, it’s as though our leaders have worked overtime making sure we’re unprepared for an inevitable energy dilemma. We’ve neglected public transportation, and many Americans who are not part of the white-collar workforce have been pushed out from expensive cities to suburbs and beyond, with no alternative other than driving everywhere. While automakers have turned their focus to manufacturing electric vehicles (EVs), these still account for a small fraction of the car market, and most of today’s gas-guzzling cars will still be on the road a decade or two from now. Crucially, there are as yet only exploratory efforts underway to transition trucking and shipping—the mainstays of global supply chains—and find more sustainable alternatives. That creates a unique vulnerability: the current worldwide diesel shortage could hammer the economy even if the government and the energy industry somehow come up with enough gasoline to keep motorists cruising to jobs and shopping malls.

Then there’s the issue of the way fossil fuels are financed. They’re not treated as a depleting public good, but as a source of profit—with investors either easily enticed to plunge into a passing mania or spooked to flee the market. Just in the past decade, investors have gone from underwriting a rapid expansion of fracking (thereby incurring massive financial losses), to insisting on fiscal responsibility, while companies are now milking profits from high prices and buying back stocks to increase their wealth. Long-term energy security be damned.

Meanwhile, the climate monster stirs fitfully. With every passing year, we have seen worsening floods, fires and droughts; glaciers that supply water to billions of people melting; and trickles of climate refugees threatening to turn into rivers. As we continue to postpone reducing the amounts of fossil fuels we burn, the cuts that would be required in order to avert irreversible climate doom become almost impossibly severe. Our “carbon budget”—the amount of carbon we can burn without risking catastrophic global warming—will be “exhausted” in about eight years at current emission rates, but only a few serious analysts believe that it would be possible to fully replace fossil fuels with energy alternatives that soon.

We need coherent, bold federal policy—which must somehow survive the political minefield that is Washington, D.C., these days. Available policies could be mapped on a coordinate plane, with the horizontal x-axis representing actions that would be most transformative and the vertical y-axis showing what actions would be most politically feasible.

High on the y-axis are actions like those that the Biden administration just took, to release 1 million barrels a day of oil from the strategic petroleum reserve and to invoke the Defense Production Act to ramp up the production of minerals needed for the electric vehicle market. While politically feasible and likely popular, these efforts won’t be transformative.

An announcement by President Joe Biden of an ambitious energy-climate vision, with the goal of eliminating our dependence on foreign fuel sources and drastically reducing carbon emissions by the end of the decade, would probably fall somewhere in the middle, where the x- and y-axes meet. Such a vision would encompass a four-pronged effort being proposed by the government:

- Incentivizing massive conservation efforts, including “Heat Pumps for Peace and Freedom” and providing inducements for businesses to implement telework broadly.

- Directing domestic production of fossil fuels increasingly toward energy transition purposes (for example, making fossil fuel subsidies contingent on how businesses are growing the percentage of these fuels being used to build low-carbon infrastructure).

- Mandating massive investments in domestic production of renewables and other energy transition technologies (including incentives to recycle materials).

- Providing an “Energy Transition Tax Credit” to households or checks to offset energy inflation, with most of the benefits going to low-income households.

Ultimately, some form of fuel rationing may be inevitable, and it is time to start discussing that and planning for it (Germany has just taken the first steps toward gas rationing)—even though this would be firmly in the x-axis territory. Rationing just means directing scarce resources toward what’s vital versus what’s discretionary. We need energy for food, critical supply chains and hospitals; not so much for vacation travel and product packaging. When people first hear the word “rationing,” many of them recoil; but, as author Stan Cox details in his history of the subject, Any Way You Slice It, rationing has been used successfully for centuries as a way to manage scarcity and alleviate poverty. The U.S. SNAP (food stamp) program is essentially a rationing system, and all sorts of materials, including gasoline, were successfully rationed during both world wars. More than two decades ago, the late British economist David Fleming proposed a system for rationing fossil fuel consumption at the national level called Tradable Energy Quotas, or TEQs, which has been discussed and researched by the British government. The system could be used to cap and reduce fossil fuel usage, distribute energy fairly and incentivize energy conservation during our transition to alternative sources.

Also, we need to transform the ways we use energy—for example, in the food system, where a reduction in fossil fuel inputs could actually lead to healthier food and soil. Over the past century or so, fossil fuels provided so much energy, and so cheaply, that humanity developed the habit of solving any problem that came along by simply utilizing more energy as a solution. Want to move people or goods faster? Just build more kerosene-burning jet planes, runways and airports. Need to defeat diseases? Just use fossil fuels to make and distribute disinfectants, antibiotics and pharmaceuticals. In a multitude of ways, we used the blunt instrument of cheap energy to bludgeon nature into conforming with our wishes. The side effects were sometimes worrisome—air and water petrochemical pollution, antibiotic-resistant microbes and ruined farm soils. But we confronted these problems with the same mindset and toolbox, using cheap energy to clean up industrial wastes, developing new antibiotics and growing food without soil. As the fossil fuel era comes to an end, the rules of the game will change. We’ll need to learn how to solve problems with ecological intelligence, mimicking and partnering with nature rather than suppressing and subverting her. High tech may continue to provide useful ways of manipulating and storing data; but, when it comes to moving and transforming physical goods and products, intelligently engineered low tech may offer better answers in the long run.

Further along the x-axis would be the daring action of nationalizing the fossil fuel industry. But at the very farthest end of the x-axis is the possibility of deliberately reining in economic growth. Policymakers typically want more growth so we can have more jobs, profits, returns on investment and tax revenues. But growing the economy (at least, the way we’ve been doing it for the past few decades) also means increasing resource extraction, pollution, land use and carbon emissions. There’s a debate among economists and scientists as to whether or not economic growth could proceed in a more sustainable way, but the general public is largely in the dark about that discussion. Only in its most recent report has the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) begun to probe the potential for “degrowth” policies to reduce carbon emissions. So far, the scorecard is easy to read: only in years of economic recession (such as in 2008 and in 2020) have carbon emissions declined. In years of economic expansion, emissions increased. Policymakers have held out the hope that if we build enough solar panels and wind turbines, these technologies will replace fossil fuels and we can have growth without emissions. Yet, in most years, the amount of increased energy usage due to economic growth has been greater than the amount of solar and wind power added to the overall energy mix, so these renewable sources ended up just supplementing, not displacing, fossil fuels. True, we could build turbines, panels and batteries faster; but, as long as overall energy usage is growing, we’re continually making the goal of reducing our reliance on fossil fuels harder to achieve.

Wouldn’t giving up growth mean steering perilously close to the Scylla of economic peril in order to avoid the Charybdis of climate doom? So far, we’ve been doing just the reverse, prizing growth while multiplying climate risks. Maybe it’s time to rethink those priorities. Post-growth economists have spent the last couple of decades enumerating the ways we could improve our quality of life while reducing our throughput of energy and materials. Policymakers must finally start to take these proposals seriously, or we will end up confronting the twin monsters—economy-crushing fossil fuel scarcity and devastating climate impacts—without prior planning and preparation.

It was always clear that we would eventually have to face the music with regard to our systemic economic dependency on depleting, polluting fossil fuels. We have delayed action, making both the economic challenge and the climate threat harder to manage. Our possible navigation channel between Scylla and Charybdis is now perilously narrow. If we wait much longer, this channel will vanish altogether.

This article was produced by Earth | Food | Life, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

The Energy/Food Crisis Is Far Worse than Most Americans Realize

Everyone who owns a gasoline-burning car has noticed that fuel prices have shot up in recent weeks. And most of us have read headlines about high energy prices driving inflation. But very few Americans have any inkling just how profound the current energy crisis already is, and is about to become.

This lack of awareness is partly due to economists, and those who depend on economists’ readings of the tea leaves of daily data (a group that, sadly, includes nearly all politicians and news purveyors). Recently I heard an NPR staff commentator confidently state: “The only way to get gasoline prices under control is to get inflation under control.” Anyone who understands recent events and how economies work will immediately realize that the statement is ass backwards. Energy prices are rising for specific physical reasons, most of which are widely reported. Those higher prices show up in economic statistics as inflation, a phenomenon that economists equate to a malevolent miasma that occasionally drifts into the economy from a mysterious alternate dimension. “Ah,” say the economists, “but we have a magic spell to drive the miasma away—higher interest rates!” The Fed’s assumption that raising interest rates will somehow reduce current high energy costs is comparable to medieval physicians’ belief that leech bloodletting would cure diseases like tuberculosis.

Of course, the goal of raising interest rates is to cool demand, which theoretically should help lower prices. But if prices for a particular commodity are rising due to physical shortage caused by novel circumstances or events rather than increasing demand, then higher interest rates may offer little relief while bringing serious unintended consequences of their own (see 1970s, “stagflation”). The comparison with leeches still stands.

There’s already enough bloodletting going on in the world. What we need now is sound thinking based in physical reality. Let’s start with symptoms and identify clear, understandable causes. Then we’ll explore the current extent of the energy crisis and its deeper societal implications, especially with regard to food. Finally, we’ll look at the energy crisis in the context of a broader, longer-term view of our economic system and see what things our leaders could do that might actually improve the prospects of ordinary citizens and future generations.

Why Prices Are Up

What’s making energy more expensive? Simple: physical scarcity resulting from pandemic, war, and depletion. Let’s unpack each of these causes.

The economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic are old news, but they keep reverberating. A persistent worker shortage, which you may have noticed at local restaurants, is also impacting energy companies and shipping firms. Further, the crash in oil demand early in the pandemic (when few people were driving to work) led to production cutbacks in the petroleum industry, notably in the US—where fracking companies had been giddily burning through investor cash for years. Now demand has recovered but investors are wary, and so companies are slow to drill wells likely to prove unprofitable. Raising interest rates—which will make it more expensive for oil companies to borrow money to fund operations—certainly won’t increase the flow of oil and gas.

The energy impacts of the Russian invasion of Ukraine are likewise straightforward and widely reported. Western oil companies have pulled out of Russia, making an ongoing decline in future Russian crude production virtually certain. The European Union has proposed a ban on oil imports from Russia, though time will tell if it can reach the consensus needed from members states, many of which are heavily dependent on Russian oil and gas. Russian production is already down by nearly 1 million barrels per day, and exports have reportedly fallen by about 4 million barrels per day. This is a substantial chunk of the world’s 100-million-barrel-per-day liquid fuel demand.

Looming back of every other aspect of the oil supply story is depletion. If there’s a shortage of oil, why not just open the spigots in other nations to make up the shortfall? Unfortunately, it’s not that simple. OPEC’s tired old wells are about half depleted following decades of continuous extraction. Increasing the rate of pumping at this point would damage reservoirs, reducing the amount ultimately recoverable. The owners and managers of those oilfields are understandably reluctant to jeopardize their patrimony—and they’re relishing the higher prices their product is selling for. So, OPEC has barely nudged its output in response to shortages brought on by the war.

The other potential source of increased supply is the US, whose tight oil extraction rates have soared in recent years. But most of the geological formations that have been the source of this bonanza (such as the Bakken in North Dakota) are already in irreversible decline due to depletion. The world as a whole saw its peak output of conventional petroleum in 2016, following a long plateau that began in 2005. Oil importers, therefore, are largely out of options for replacing those lost Russian barrels.

There are some other factors complicating the current fuel supply system. I’ve focused on oil, simply because it’s the most globally traded of fuels and delivers the most energy to society. But supplies of natural gas are also being hammered as a result of the war, with prices already at record levels and poised to soar even higher. The “normal” price for natural gas in the US is about $2.50 per million BTUs; today gas is selling at three times that level, with other nations seeing gas trade at over $15. I’ll discuss some consequences of that below.

Further wrinkles have to do with diesel fuel, which is essential for trucking and hence global supply chains; and jet fuel (kerosene), which powers global aviation. Diesel and kerosene are made up of relatively long molecular hydrocarbon chains, but the light tight oil that the US has brought to market in recent years from fracking contains mostly short-chain molecules. Gradually, as world conventional oil production has plateaued and started to decline, with US light tight oil providing the main source of growth, diesel and kerosene output have stalled and sputtered. Diesel and kerosene prices have risen to unprecedented levels, and there are clear and persistent signs of worldwide shortage.

How Bad Is It?

Energy is essential for everything we do. It’s not just a part of the economy; in a real, physical sense it is the economy. Therefore, whenever there’s an energy crisis, it can quickly become an everything crisis.

The links between energy and the economy are perhaps at their most transparent when it comes to diesel fuel. Trucks, freight trains, and tractors burn diesel. Therefore, when diesel gets scarce, supply chains start to seize up and food prices climb.

Shipping costs were already soaring before the Russia-Ukraine war. Now, diesel shortages are erupting in South Africa, Sri Lanka, and Europe. Passenger trains in India have been idled. Thousands of buses, trucks, and cars in Cameroon have been stranded for weeks without fuel. In Sri Lanka, high energy and food prices have just helped bring down a government.

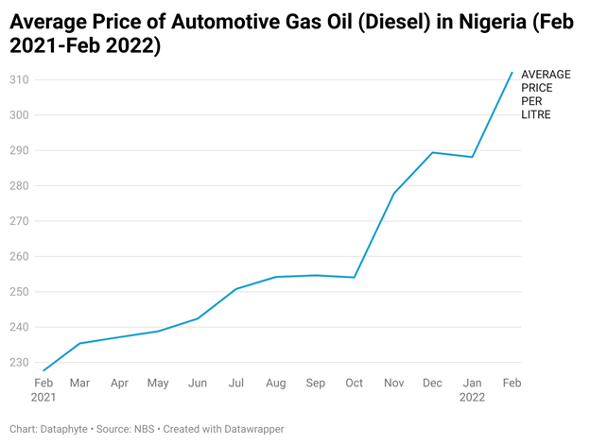

Cost of diesel in Nigeria (a major oil producing country) https://www.dataphyte.com/latest-reports/energy/chartoftheday-diesel-price-has-gone-up-by-36-98-in-1-year/

At the start of May, inventories of diesel on the US east coast plunged to the lowest seasonal level since government records began more three decades ago. Wholesale and retail diesel prices hit all-time highs.

Among the millions of trucks that run on diesel are Amazon.com’s roughly 70,000 delivery vans and semi-trucks. That company just announced a disappointing quarter and outlook due largely to higher costs for trucking packages to customers.

Most of us don’t really care much whether Amazon turns a profit. But Jeff Bezos’s current woes are echoed throughout industry after industry. Even companies whose business model doesn’t include physical delivery of goods still depend on other companies that burn diesel. That’s partly why global stock markets have recently seen massive sell-offs. But the market has yet to fully internalize the nearly existential risk posed by declining energy.

The signs of energy crisis are everywhere. In Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country, airlines recently threatened to cancel virtually all flights in response to surging kerosene prices. US retail gasoline prices just hit a new record. And Europe is preparing for the likelihood of severe natural gas shortages next winter.

Saudi energy minister Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman, speaking at the World Utilities Congress in Abu Dhabi in early May, said, “The world needs to wake up. The world is running out of energy capacity at all levels. It is a reality.” One may question the motives of the Saudi minister: a so-called “NOPEC” bill making its way through the US Congress would make it possible to sue the OPEC cartel for price fixing, so the Saudis might like to heighten the perception that they are providing the world with an increasingly scarce good. Nevertheless, the prince’s statement is clear, direct, and supported by abundant evidence.

Food and Energy

If tractor fuel is getting more expensive, you might think that would put pressure on food prices—and you’d be right. But that’s only one reason the cost of food is skyrocketing.

Nitrogen fertilizer, made from natural gas, is seeing unprecedented price hikes, largely as a result of the Russia-Ukraine war. In response, farmers everywhere are preparing to test the limits of how little fertilizer they can apply without threatening yields. Forecasts are bleak. For West Africa, reduced fertilizer use is projected to shrink this year’s rice and corn harvest by a third. Costa Rica could see coffee output falling as much as 15 percent next year if farmers reduce their fertilizer application by one-third.

For many years, organic and ecological agriculture advocates have argued that the world could produce just as much food without resorting to fossil fuel-based fertilizers and pesticides. But their alternative methods require knowledge and time for transition. Going cold turkey on fertilizer without planning and preparation will almost certainly lead to sharply lower yields over the short term. In response, the EU is now delaying rules intended to reduce farming’s environmental impacts, including curbs on pesticide use. It also aims to put four million hectares of fallow land into cultivation.

Food security is being threatened by problems with distribution chains for all the inputs into agricultural system—from spare parts to packaging to cooking fuel. Once again, as with energy prices, there are several mutually interacting causes, including lingering effects of the pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine war. The latter has led to the loss of wheat shipments from Ukraine and Russia, which together are responsible for nearly 30 percent of world supplies. Recently, Russia has rained missiles on Odesa, a major port for grain shipments, further disrupting global food distribution.

Altogether, foods exported from Russia and Ukraine normally account for more than 10 percent of all calories traded globally. The two countries also export a significant portion of the world’s vegetable oils used in cooking and preparing food. As a result of the conflict, there are now shortages of sunflower oil in Europe, and supermarkets in the UK are limiting purchases of cooking oil.

Low-income countries that were already destabilized by economic havoc from the pandemic are seeing further shocks now from higher food prices. Egypt is considering raising the price of subsidized bread for the first time in four decades, even though the subsidy is widely credited with keeping social unrest at bay.

In the wake of the Russia-Ukraine war, dozens of countries—including Hungary, Indonesia, Moldova, and Serbia—have thrown up trade barriers to protect domestic supplies of grains, fruits, vegetables, cooking oils, and nuts. While these barriers are intended to protect domestic food supplies, their collective result is to put more pressure on global prices.

Of course, all of this added food insecurity comes as our weather becomes weirder year by year. China’s wheat harvest this season is uncertain due to extreme rains in recent months, and, with global wheat prices already up 80 percent, a lot is at stake not just for the world’s most populous nation, but also for integrated global wheat markets. Meanwhile, Somalia, which imports nearly all its wheat from Ukraine and Russia, is suffering its worst drought in years.

In sum, experts are warning of the worst global food crisis since WWII. It is a crisis that will have its severest impacts on the poorest countries, and poor people in relatively wealthy countries, especially those already experiencing food insecurity. There will also likely be compounding social and political consequences, as pointed out in a new report by risk consultancy Verisk Maplecroft, which notes that middle-income countries such as Brazil and Egypt will be particularly at risk for rising civil unrest.

Why the Big Picture Is Essential

Most news articles treat diesel, gasoline, and food price hikes as transitory phenomena. After all, historically whenever prices have gone up, they’ve later settled back down. Temporary shortages inspire innovation and trigger investment. It’s the magic of the market. So, once the pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine war are in our rear-view mirror, we can all surely get back to normal.

Missing from those articles is a systemic understanding of our current crisis. The big picture of our energy situation is perhaps best captured by a study published seven years ago, “Human Domination of the Biosphere: Rapid Discharge of the Earth-Space Battery Foretells the Future of Humankind.” Lead author John Schramski, an associate professor in the University of Georgia’s College of Engineering, likened Earth to a battery that has been charged slowly over billions of years. “The sun’s energy is stored in plants and fossil fuels,” says Schramski, “but humans are draining energy much faster than it can be replenished”—mostly by deforestation and the burning of coal, oil, and natural gas. Once that battery is discharged, there is nothing humans can do within a relevant timescale to maintain the energy flows that currently support complex industrial civilization and a population measured in billions.

No doubt there will be some temporary work-arounds. Solar and wind energy sources could substitute for fossil fuels in some applications, though material limits would prevent a full-scale replacement. But there really is no solution to our energy crisis, if by “solution” we mean a return to how energy markets have functioned during the past few decades. We are victims of systemic dependency on depleting fuels and minerals, and an economic model founded on unsustainable growth.

Once we understand that, then it’s possible to chart a course of adaptation that minimizes suffering and destruction. Instead of prioritizing growth, we must aim for rapid reduction in overall energy usage, with an emphasis on equity—both equity between the rich and poor within nations and globally. As I’ve written elsewhere, efforts should center on rationing increasingly scarce resources and developing local cooperative organizations of all kinds. Learn to work with nature and heal ecosystems.

Crises make incumbent politicians look bad. But denying or politicizing problems that result from our own prior mistakes just makes those problems worse. Here’s some free advice for policy makers and members of the Fourth Estate: take the long view, even if it’s scary. And tell the truth, even if it means losing an election or Twitter followers.

Teaser photo credit: James Gillray, Britannia between Scylla and Charybdis (1793). By James Gillray – Library of Congress, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2285374

![[Power book cover]](https://richardheinberg.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/cover_POWERcatalog-proof_300x450.jpg)