MuseLetter #359 / February 2023 by Richard Heinberg

Download printable PDF version

This month’s Museletter leads with an article looking at various debt timebombs threatening us all. It also includes the concluding part of my trilogy written for Independent Media Institute on the renewable energy transition (parts 1 and 2 were included in Museletter #356, The Final Doubling).

Converging Debt Crises

An enormous debt bomb threatens the US federal government and the nation’s financial system unless warring politicians can agree on a plan to defuse it. However, there are even bigger debt bombs ticking away beneath us all, of which fewer people are aware. It may be impossible to disarm all of them, but action is required to minimize the casualties.

Let’s start by focusing on the immediate US debt threat, then widen our view to take in longer-term and more serious liabilities that have the potential to bring down the entire global industrial economy.

Congressional Hostage Takers

The United States government reached its congressionally mandated legal debt limit, $31.4 trillion, on January 19th. This debt represents past spending: cutting the budget now won’t make the debt go away. If Congress fails to raise the debt limit, the federal government could default on its debt payments—something it has never done before.

The federal debt limit was created by Congress in 1917. In recent decades, there have been periodic standoffs (in 1985, 1997, 2011, and 2013), in which Republicans threatened to let the deadline to increase the limit pass unless Democrats agreed to spending cuts in social programs. Neither side actually wanted the federal government to default, but brinksmanship served partisan interests. This time, some Republican House Freedom Caucus members appear to regard an actual debt default (not just the threat of one) as a useful tool to force major government spending cuts.

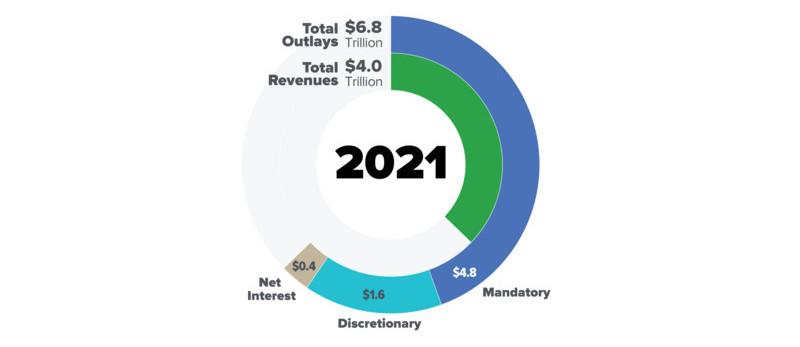

Government spending comes in three large categories—mandatory, discretionary, and interest payments. Most federal spending is mandatory, including Social Security and Medicare payments. Of discretionary spending, defense accounts for more than half. Interest payments on US debt comprise the smallest of the three categories of spending, but it is growing fast and may overtake the military budget by 2025 or 2026.Some pundits equate debt ceiling fights with hostage negotiations. In this instance, House Speaker McCarthy may have limited ability to prevent his more radical colleagues from metaphorically shooting their captive. McCarthy’s leadership is fragile and in order to gain it, he agreed to rules that will give extremists outsized influence in upcoming negotiations. A single member will be able to force a vote on the speakership, possibly plunging the entire body back into days of voting to establish a new leader.

Since US debt (in the form of bonds and other securities) anchors the global financial system, a default could rattle economies across the globe. Americans could face a recession, and stock and bond markets would likely plunge. Still, exactly how a default would play out is uncertain. Since the US government’s payment of its financial obligations is mandated in the US constitution, it is conceivable that a default could be averted by the courts. Nevertheless, there is a very real possibility that not only Americans, but millions or billions around the globe could face hardship as a result of political hardball tactics playing out in Washington DC.

The debt ceiling standoff in America is unquestionably a volatile situation, but it’s only one aspect of the larger debt crisis facing humanity.

Global Debt: Growing to Extremes

According to the late anthropologist David Graeber, debt has been around for about five thousand years. Debt is the flipside of money: especially in the modern world, where almost all money is created via bank loans, it’s impossible to have one without the other. In societies that use money, a pattern has played out again and again. At first, debt and money enable the expansion of trade and the creation of wealth. Then debt begins to accumulate faster than the ability to repay it, simply because it’s physically easier to borrow and spend than it is to extract resources and transform them with labor. Finally, a round of debt defaults destroys money and real wealth, leading to widespread misery. Eventually, the cycle begins again. Over the past two centuries, and especially since 1950, the world has seen the highest rate of production of goods and services in all history. While technology played a role, the key enabler was cheap, abundant energy from fossil fuels. During this period, GDP was generally adopted as a measure of economic success, and growth became normalized. Because it was assumed that the economy would continue to grow, it was generally believed that most debt incurred now could be repaid in the future. Further, increasing household debt (including credit card debt, mortgages, and student loans) enabled most people to consume now and pay later, and helped expand the whole economy.

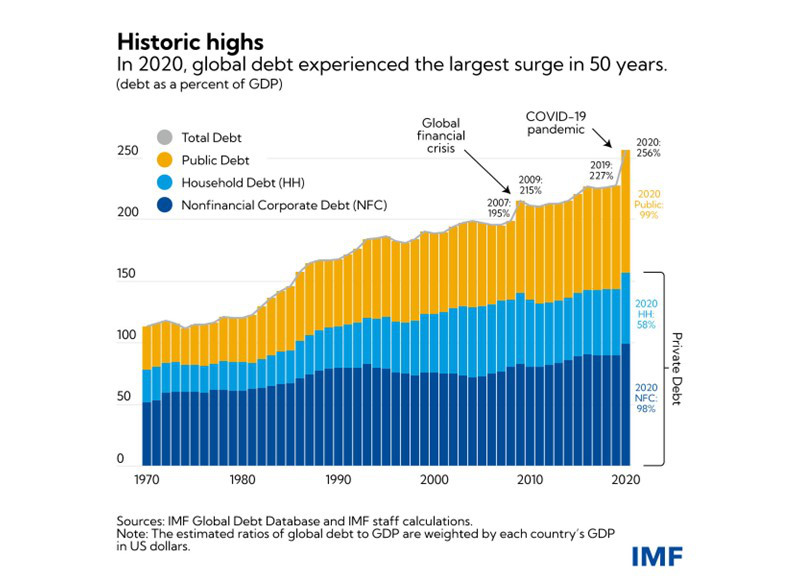

This IMF graph breaks total debt into three categories: government (also called “public”), corporate, and household. It also measures debt not simply in terms of money owed, but by the debt-to-GDP ratio. Not only has debt grown in raw numerical terms, but it has also grown in comparison with GDP. Many economists believe that high debt-to-GDP ratios can be cause for concern, since they are often associated with debt bubbles—which usually end in debt deflation, causing bank runs or a currency crisis. Examples include the 1920s stock market bubble (which triggered the Great Depression) and the US housing bubble (which caused the Great Recession).

Most current debt is, in effect, a bet on future growth. But future growth is increasingly problematic. As I have explained elsewhere (in this book and in this article), global growth is coming to an end in the first decades of the current century due to depletion of fossil fuels and other resources, rising pollution levels, and declining population growth. China, whose population has started shrinking and whose recently spectacular levels of economic growth are now rapidly tapering off, is a global bellwether. High levels of global debt are likely to turn what could be a controllable shift from expansion to contraction into a blowout of unfulfilled expectations and obligations, leading to widespread suffering.

Theft Debt—Three Vast Ways of Stealing

Debt is typically defined as a formal or informal agreement in which one party gives another something of value now, with the expectation of repayment (often with interest) at a later date. If no repayment is wanted or expected, we call the transfer a gift. But sometimes value is taken without agreement between the parties involved. Stealing and looting aren’t accompanied by negotiations over interest rates, or by mutual record-keeping. There are legal forms of taking, such as taxes and fines. But where there is no legal basis for taking something of value, societies around the world through history have recognized a moral responsibility on the part of the taker to make restitution, either symbolic or in kind, or both.

For theft debt there can be no default in the legal sense, since default is the breaking of an agreement to repay a debt, and here there has been no agreement. However, there can indeed be consequences of unrepaid theft debt. Indeed, if theft occurs on a large enough scale, those consequences may include the breakdown and collapse of societies and ecosystems.

Three categories of theft debt are relevant here: the debt of high-consuming nations to low-consuming nations, the debt of recent generations to future generations, and the debt of humanity to other species.

Especially since the start of European exploration and colonization five hundred years ago, rich nations have derived most of their wealth from natural resources and cheap labor in poor nations (indeed, in many cases the latter nations were made poor by this predatory relationship, which was often militarily enforced). As economic anthropologist Jason Hickel points out, today the Global South contributes about 80 percent of the labor and resources for the world economy, yet the people who render that labor and those resources receive about 5 percent of the income the global economy generates each year. Eventually, the deliberate impoverishment of a population by wealthy exploiters tends to lead to resentment and rebellion among those exploited, and corruption and moral decline among the exploiters.

The transfer of wealth also occurs intergenerationally. When people today use or degrade renewable resources (such as forests, fish, aquifers, and soil) faster than nature can regenerate them, this make it more difficult for people in the future to enjoy equivalent levels of wealth. Nonrenewable resources, such as minerals and metals, can be recycled to a certain extent, but are typically just dispersed into the environment as we use them, making it difficult or impossible for the next generation to access them. We are leaving our grandchildren a depleted and more polluted world, with global ecosystems now stewing in thousands of human-produced chemicals of varying degrees of toxicity. Since natural resources are the ultimate basis of all wealth creation, this means we are, in effect, stealing from the future. Young people are starting to get the message: surveys say that more than two thirds of Americans believe today’s children will be financially worse off than their parents.

Humanity also, in effect, takes from other species by degrading or transforming habitat. Animals and plants are always jostling amongst themselves within ecosystems, now cooperating, now competing, with some expanding their populations and others losing out. However, humanity, with its astounding fossil-fueled success at population expansion, is taking over habitable space to a degree that threatens not only other species, but our own as well—since humanity depends on healthy and diverse ecosystems for a range of free services such as pollination, pest management, and flood control. Nonhuman animal species have lost, on average, 70 percent of their members in the past 50 years, marking a nearly unprecedented transfer of habitat from millions of species to just a handful—Homo sapiens and the animals and plants it has domesticated.

These three forms of taking are often perfectly legal, because it is usually the beneficiaries (i.e., privileged humans alive today) who make the laws. But legal theft is still theft, and there will be consequences.

Paying Back, Paying Forward

Debt buildups are often likened to soap bubbles. When a soap bubble bursts, a tiny hole expands during a brief fraction of a second, then suddenly the bubble is gone. As the bubble initially inflates, there’s no reason (other than past experience and complex calculations having to do with fluid mechanics) to expect that this magical shiny sphere will soon disappear. Debt bubbles are like that too: they can take some time to inflate, and during that period, there may be little apparent cause for worry (except among historians or ecologists). Then suddenly, financial hell breaks loose. People who understand the mechanics of bubbles, physical or metaphoric, say that the only way to avoid a nasty bursting is somehow to deflate the bubble harmlessly before it pops.

That’s often easier in theory than in practice. What about the US federal government’s debt bubble? If the government were to rein in its spending significantly, there would be consequences—perhaps including lost jobs in the defense industry and reductions in the security or health of those who receive support payments of various kinds. Modern monetary theorists say it is possible to avoid both potential defaults and the need to make severe spending cuts simply by empowering government to create the money it needs without having to borrow it at interest. But while money may theoretically be easy to create, resources and energy are different matters altogether. And, in the end, money works only when it reliably represents access to energy and resources. If the money supply grows but resources don’t, the result can be runaway inflation. For the US, modern monetary theory could provide some temporary and partial relief from the government debt crisis, but over the long run there is no getting past the requirement to reduce overall national consumption—and that is likely to provoke a political crisis. That political crisis could be headed off in part by developing rationing systems and by shifting the aim of economic policy away from GDP growth and toward general happiness and cooperation.

The world’s vast increase in financial debt over the past few decades ultimately can be resolved only by a round of defaults, or by a deliberate process of debt forgiveness and deleveraging, like the debt jubilees that ancient societies held on a regular basis. The former would lead to widespread bankruptcies and would endanger the entire economy; the latter would, in effect, constitute a destruction of some existing wealth and a transfer of much of what’s left of that wealth from the rich to the poor. Such a process might best begin with a redistribution of most of the wealth of the billionaire class.

Theft debt cannot be “forgiven”; there are only two possible outcomes: repayment or consequences.

For international theft debt, repayment would require wealth transfers from rich to poor nations, starting with the cancellation of poor nations’ debts. Reparations for slavery and land theft might constitute a key part of this much larger process of global leveling.

Generational theft debt cannot be repaid by somehow replacing nonrenewable resources already depleted: we can’t put ores back in the ground (though with renewable resources, we could help forests and fisheries recover). More meaningfully, we could make a start at easing the lives of those who will come after us by creating a way of life that’s peaceful, sustainable, cooperative, and beautiful. In many respects, that would be a more valuable legacy than material abundance. And the sooner we start, the more of a legacy we leave them.

Our theft debts to other species likewise probably cannot be repaid in kind, at least not entirely: there is little likelihood, for example, that we will be able to use modern genetics to revive large numbers of species we’ve already driven into extinction, unless we can provide those revived species with appropriate habitat. But we can stop running up our tab on nature. That might mean ceding half the Earth to ecosystem recovery.

Absent such efforts, bubbles will continue to inflate until they burst. In that case, the worst outcomes can be averted only by starting now to build personal, household, ecosystem, and community resilience.

A realistic ‘energy transition’ is to get better at using less of it

In 2022, I authored two articles expressing doubts about society’s transition from fossil fuels to renewable solar and wind power. In this final article in the series, I’ll explain why my conclusions are based on experience as well as analysis.

My gloomy assessment of the prospects for renewable energy is not motivated by love of fossil fuels. In fact, I’ve spent the past two decades writing books and articles and giving hundreds of talks arguing that our collective adoption of coal, oil, and gas was the biggest mistake in human history. However, I don’t think, as some spokespeople for environmental organizations sometimes seem to do, that any criticism of alternative energy sources is a form of climate denialism.

At the other extreme, I disagree with the few hard-core environmentalists who believe that renewables are a complete dead end. After humanity’s fossil-fueled fever has eventually broken, we will return to renewable energy, one way or another. We’ve relied on renewable energy for untold millennia in terms of food, firewood, wind, and flowing water. It certainly would be preferable if we could partially transition to forms of renewable energy that would enable us to maintain some of the best of what we’ve accomplished over the past few energy-intensive decades—including scientific knowledge and creative works produced in a growing host of media, from sound recording to motion pictures to digital art. Unfortunately, that will be impossible without functioning electricity grids, which are challenging to maintain even in the best of times. If we could use hydro, solar, wind, and geothermal energy to power slimmed-down grids, that would greatly ease the transition away from fossil fuels.

In short, I have no reason to dislike renewable energy. In fact, I love it. And I live with it.

My wife Janet and I have had solar panels on the roof of our house for so long that the first set aged to become antiques; recently, we replaced that still-working initial set—which we donated to a good cause—with a new one that was cheaper and far more efficient. We have a solar hot-water heater, a solar cooker, and a solar food dryer; we heat and cool our home with a solar-powered electric heat pump, and we drive an electric car. We went solar not for the purpose of virtue signaling, but in order to use our household as a laboratory. And the experiments have been not only instructive but also enjoyable. We would never willingly go back to using the fossil fuel-based technologies we ditched.

However, being an early adopter of solar technology has given me personal insight into some of the practical limitations and difficulties of making the energy transition. For example, proponents of the Inflation Reduction Act (President Joe Biden’s main legislative effort to boost the shift toward renewables) point out that the government can’t be expected to pay for the transition entirely on its own; rather, the idea is for government incentives to prime the national economic pump so that companies and households will be incentivized to do the heavy spending that will be necessary to ensure this transition.

But what level of spending on the part of the companies and the public is realistic? I can only cite Janet’s and my own experience: we’ve spent tens of thousands of dollars on our personal energy transition, even though we did things as cheaply as possible, and even though various financial incentives were already being offered by the government. Bigger tax breaks would have helped. But not every household will be installing a new mini split HVAC system or induction stove or replacing its cars (the average U.S. household has two of them) in the next few years. Similarly, not every company will want to replace its fleets of vehicles (including long-haul trucks, ships, and airliners) or abandon its sunken investments in other machinery—possibly including cement kilns and blast furnaces.

In addition to my renewable experiments at home, I also explored the feasibility of transitioning away from fossil fuels while working on the 2016 book Our Renewable Future with David Fridley of the Energy Analysis Program at California’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. We engaged in researching renewable energy over the course of the previous year, during which time I would propose questions to which Fridley could use technical analysis to answer.

I asked Fridley how the consumer electronics industry can proceed without fossil fuels. I also asked him how our food system can adapt, given the vital importance of nitrogen fertilizers currently made with natural gas. Fridley did the research and math and often came up with sobering answers. We concluded that nearly all the technical problems entailed in making these transitions can be solved at the laboratory scale. What do I mean by “laboratory scale”? For example, it’s possible to use solar electricity to make synthetic hydrogen-based fuels that can be used to keep airliners flying. However, in many cases, ramping up such solutions to the vast industrial scale, which is necessary to maintain global business-as-usual status, is probably unrealistic. In rich countries like the U.S., the transition will only be feasible if we cut energy usage dramatically, especially for certain transportation modes (aviation) and industrial sectors (concrete and steel), while completely redesigning truly essential sectors (notably, our food system).

One thing Janet and I realized early on in our home energy transition experiment was that most of the fossil fuel energy usage that sustains our household is not under our control. In our house, we don’t do any mining, heavy manufacturing, road construction, or industrial agriculture. We can’t even make the glass for our solar cookers. Other people do those things; and, after carefully monitoring the relevant industries over the past 20 years, I’ve concluded that those other people are taking only tiny steps toward eliminating fossil fuels. The next 20 years may see more vigorous efforts in that direction, but the inertia is enormous.

In my personal view, energy transition planning is now based far too much on abstract computer-based models that fail to include all the relevant factors. It’s relatively easy to project renewable energy growth trends using a spreadsheet; but, beyond the easy phases that Janet and I have undertaken, the actual implementation will imply vast changes in materials supply chains and manufacturing processes—shifts that will be disruptive in the best case, and nearly impossible in the worst.

As I’ve suggested before, we need integrated pilot projects to identify major potential snags in the energy transition process. An ideal project would be to retrofit a medium-sized industrial city so it runs not just its electrical power system on renewables but also its transport and food systems, with sunlight and wind also supplying heat for its homes. The concrete for its roads and buildings would be made using renewable electricity, as would the glass for its windows.

The fact that there are no such pilot projects currently in operation is a clue that there are systemic roadblocks relating to large-scale interlocking technological systems that will make it hard and costly to wean from fossil fuels. In some respects, the energy transition is analogous to redesigning and rebuilding an airplane while it’s in flight.

Household experience is currently about the closest thing we have to operating pilot projects. So, do the experiment yourself. Go solar. But notice how much energy you use and what you use it for; also, pay attention to what energy you can control, and what you can’t. You may discover, as Janet and I have, that your most impactful efforts to reduce your carbon footprint involve simply reducing your travel and consumption.

My aim is not to discourage people working toward an energy transition, but to insist that we develop a realistic plan for energy descent, rather than insisting on foolish dreams of eternal consumer abundance by means other than fossil fuels. Currently, politically rooted insistence on continued economic growth is discouraging truth-telling and serious planning for how to live well with less.

This article was produced by Earth | Food | Life, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

Photo by 2 Bull Photography on Unsplash

![[Power book cover]](https://richardheinberg.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/cover_POWERcatalog-proof_300x450.jpg)