MuseLetter #297 / February 2017 by Richard Heinberg

This month’s Museletter brings together three essays that sound alarms on the early days of the Trump administration.

Download printable PDF version here (PDF, 177 KB)

Awaiting Our Own Reichstag Fire

Millions of Americans now share the profoundly disturbing experience of watching and waiting as their nation lurches toward authoritarianism. In a previous essay, I described the Trump administration as a “presidency in search of an emergency”—i.e., a crisis that could be used as a pretext for seizing unchecked power. I opined that the emergency could come in the form of an economic meltdown, a terrorist attack, or a natural disaster.

As a result of the events of the last two weeks we now know what the crisis will almost certainly be (a terrorist attack) and how it will be used—namely, to do the following:

- Nullify the constitutionally mandated independence and authority of the courts. More on this below.

- Shut down congressional investigations. These are soon likely to include probes into collusion with Russia to influence the election (if the worst of the allegations are substantiated, Senators and Representatives could soon be bandying a word that starts with “T” and rhymes with “reason”), along with financial conflicts of interest that go vastly beyond the recent dustup with Nordstrom’s. The evidence of profound misdeeds is getting so hard to ignore that even a Republican Congress will likely eventually get rambunctious. The forced departure of national security adviser Michael Flynn can only fan the furor, rather than quelling it (again, more below).

- Criminalize dissent. Millions have already taken to the streets to voice their displeasure with the new administration, and thousands are showing up regularly at congressional town hall meetings. The time-proven ways authoritarian governments discourage anti-government activism are to increase surveillance and to heighten the perceived risks entailed in joining protests (prison time or worse).

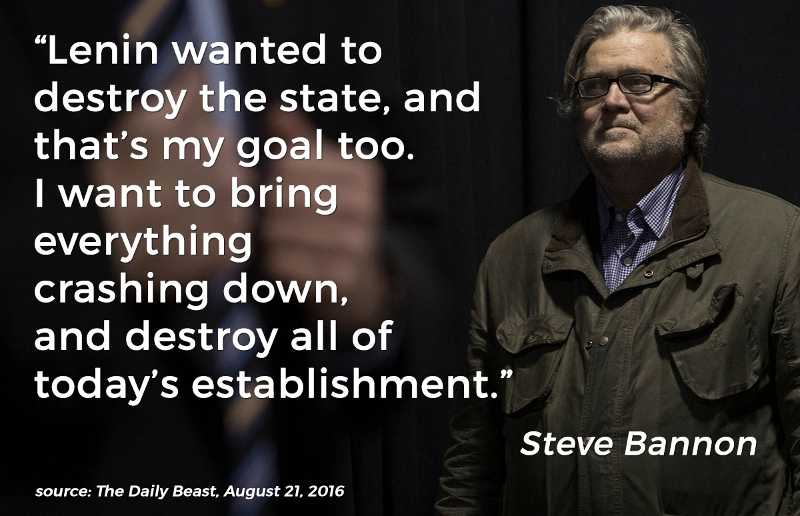

- Rein in and discredit the mainstream media. White House strategist Steve Bannon has called the media “the opposition party.” Authoritarian regimes always attempt to marginalize and control the press and broadcasters. Given a sufficiently compelling national emergency, criticism of the government could be declared unpatriotic and even criminalized (as happened during World War I).

The events of the week of February 6 provided some clues on how Trump’s war on the judiciary is likely to play out. Jack Goldsmith writes that the way the executive order banning entry by residents of seven Muslim-dominated nations was drafted suggests a couple of possible interpretations. One is that White House Counsel Donald McGahn is simply incompetent; the other is that the executive order was deliberately botched in order to flush out judicial opposition for later retribution: “….Trump [may be] setting the scene to blame judges after an attack that has any conceivable connection to immigration. If Trump loses in court he credibly will say to the American people that he tried and failed to create tighter immigration controls. This will deflect blame for the attack. And it will also help Trump to enhance his power after the attack.”

In a New York Times column titled “When the Fire Comes,” Paul Krugman recalls that “The Bush administration exploited the post-9/11 rush of patriotism to take America into an unrelated war, then used the initial illusion of success in that war to ram through huge tax cuts for the wealthy.” He opines, “the consequences if Donald Trump finds himself similarly empowered will be incomparably worse.”

Krugman might easily have dug a bit further back in history to mention the Reichstag Fire of 1933, which Hitler and the Nazis used as an excuse to suspend civil liberties and round up enemies. Some historians now believe the Nazis planned the arson as a false flag operation.

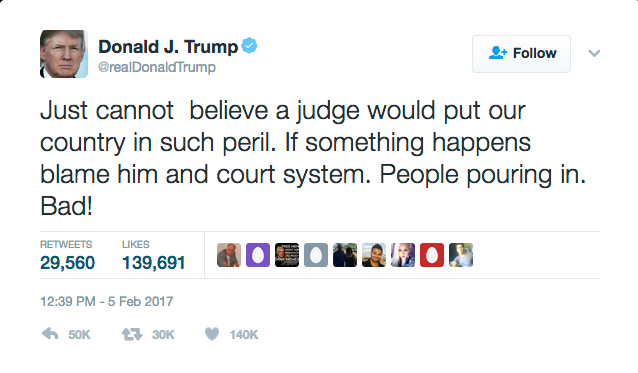

I’m not suggesting that Trump can or will do something of the sort. But by demonizing Muslims, Trump has implicitly invited some sort of attack. Indeed, he almost literally does so in this tweet:

All of this speaks to the new administration’s evident intent to go full authoritarian on us. But success in carrying through with such intent is far from guaranteed. Donald Trump stands at the head of a cadre of insurgents that has managed to seize an extraordinary level of power in a very short time, but he and his merry band are opposed by an old guard that is not likely to exit the stage quietly or willingly. That old guard includes appointed officials and career staffers in Executive Branch agencies including the Justice Department, FBI, CIA, NSA, and DHS. Each agency has its own institutional agenda that is independent of the White House. To succeed, Trump’s team must neutralize, co-opt, enlist, or replace as much of this bureaucracy as possible, as quickly as possible. Indeed, Trump has already completely restructured the National Security Council in a way that is completely unprecedented: White House strategist Steve Bannon and Chief of Staff Reince Priebus have been given permanent seats on the NSC’s Principals Committee, while the Director of National Intelligence and the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff are now to be included in meetings only when requested for their expertise; the Secretary of Energy and the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations are excluded entirely. Meanwhile, the White House has purged nearly the entire State Department senior staff. So far, most observers agree the job of transforming the Executive Branch is proceeding in fits and starts, and suffers from poor planning and leadership.

In addition, there is Congress to manage. The Democratic Party is of course utterly opposed to the new administration, but it’s sidelined with little real power; meanwhile, though Trump is a Republican and has captured the presidency for his party, his crew is by no means entirely in sync with the old Republican guard. Indeed, top Republican senators have called for a probe of the Flynn/Russia situation. For now, Congress is largely still working in line with the White House—but its acquiescence is not to be taken for granted.

Next comes the Judiciary. It will simply take too long to replace enough federal judges so as to entirely neutralize opposition within this branch of government, even given the imminent prospect of a conservative-dominated Supreme Court. That’s why silencing the judiciary in the aftermath of a national emergency makes sense.

Finally there are the American people. No regime can afford to entirely ignore the will of the public. Within the White House, the faction around chief strategist Stephen Bannon appears to be consolidating power and keeping the faith of Trump voters by forging ahead with campaign promises to expand the Mexican border wall, bar entrants from Muslim countries, step up deportations of undocumented residents, and downshift the NATO alliance. Nevertheless, popular opposition to Trump is very large and growing, and even in the face of a national emergency this could pose a significant obstacle to the administration’s plans.

It must always be borne in mind that the true objectives of the Trump administration differ somewhat from the issues that energized Trump voters. White House strategy almost certainly includes doing away with regulatory constraints on global banking while privileging U.S. banks and corporations wherever possible. The Trumpists also hope to fan economic growth with a combination of increased fossil fuel production, a trillion-dollar infrastructure plan, and a revitalization of American manufacturing. Trump’s foreign policy strategy evidently includes partnering with Russia on oil and gas projects and on fighting ISIS in Syria, while also driving a wedge between Russia and China wherever possible. At the same time, White House strategists seem intent on pursuing a civilizational war with Islam. Every autocrat needs a villain, and Iran is being set up in the role of immediate and proxy foe. The ultimate prize is the Middle East’s remaining oil, which Trump has said we should “take”—whatever that means in practical terms.

Not all of this is completely anathema to the existing Washington consensus. As Nafeez Mossadeq Ahmed argues, the Trump crew actually represents an existing segment of the Washington elite, “…an interlocking network of powerful players across sectors which heavily intersect with the Deep State: finance, energy, military intelligence, private defense, white nationalist ‘alt-right’ media, and Deep State policy intellectuals.” Ahmed believes “we are seeing a powerful military-corporate nexus within the American Deep State come to the fore. Trump, in this context, is a tool to re-organize and restructure the Deep State in reaction to what this faction believe[s] to be an escalating crisis in the global Deep System.” The guiding philosophy of this far-right nexus, which has exponents in Europe and Russia as well, has been labeled “traditionalism”—an ideology I hope to unpack in my next essay.

Flynn is an early casualty of infighting among elites within the Executive Branch. But he won’t be the last. Intelligence professionals appear to be deliberately withholding daily information from the president (who seems minimally interested in any case). Leaks are helping to undermine morale (it was a White House leak that brought Flynn down). The sharks are circling and there is blood in the water. If it is to succeed, the Trump presidency needs its emergency sooner rather than later. Even then there is no sure prospect of maintaining control for long.

It’s important to remember that the elites with whom the Trump insurgency is at war have failed in their objectives and have misled the American people for many years. Neoconservative foreign policy was responsible for needless and failed wars, as well as a steady stream of lies that squandered public credibility and support; meanwhile, neoliberal economic policy oversaw the erosion of the American middle class through globalization and financialization. It is these entrenched elites, for whom Hillary Clinton served as a lightning rod, who are therefore ultimately responsible for Trump’s ascendancy.

It may be a mistake to assume that one faction or the other will prevail. At least, that’s the implication of a recent essay by Peter Turchin, a Russian-American ecologist specializing in the study of cultural evolution. Without specific reference to the Trump insurgency, Turchin posits that America has entered a period of greatly heightened intra-elite competition, one measure of which is the vast recent increase in sums spent on election races. There is always competition among elites for positions of authority and power, but when positions are limited and aspirants are many, the result is a breakdown of social norms and the appearance of competing power networks “which increasingly subvert the rules of political engagement to get ahead of the opposition.” Once societies enter such phases, there is no return. Elites cannibalize society’s resources in rivalry over power, resulting in a breakdown of the myriad daily instances of cooperation that enable society to function. The re-establishment of intra-elite cooperation never occurs, and the state disintegrates. Turchin’s theory (developed from Jack Goldstone’s earlier work) has been tested on data from Ancient Rome, Egypt, and Mesopotamia; medieval England, France, and China; European and Russian revolutions during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries; and the Arab Spring uprisings.

Steve Bannon has declared that he wants to “bring everything crashing down, and destroy all of today’s establishment,” but he evidently wants to do so in service to his vision of a restored white, Christian, hierarchical order ruled by a spiritually superior caste (again, more about this next week). However, as Nafeez Ahmed argues in his recent book Failing States, Collapsing Systems: Biophysical Triggers of Political Violence, we are actually facing not a “clash of civilizations” (Islam versus the Christian West) but rather a “crisis of civilization.” The former can at most merely temporarily disguise the latter. Our real crisis, only partly acknowledged or understood by any of the elites, consists of the end of the fossil fuel era, the end of economic growth as we knew it during the 20th century, and ultimately the end of an entire phase of human social and economic organization.

In this war of the elites, those who understand the “crisis of civilization” and are working to build community resilience as a response should be wary of hyper-partisanship. It may be essential over the short run to oppose both the rise of an authoritarian state and the dismantling of national climate policy. But no matter how fierce the contest, it is vital to remember that getting rid of Donald Trump will not make America great again. The only way forward with any prospect of success consists of creating a new pattern of existence within the shell of the existing one—a way of life that doesn’t require endless fossil-fueled economic growth or consumerism, and that brings people together rather than pitting them against one another.

The Über-Lie

Our new American president is famous for spinning whoppers. Falsehoods, fabrications, distortions, deceptions—they’re all in a day’s work. The result is an increasingly adversarial relationship between the administration and the press, which may in fact be the point of the exercise: as conservative commenter Scott McKay suggests in The American Spectator, “The hacks covering Trump are as lazy as they are partisan, so feeding them . . . manufactured controversies over [the size of] inaugural crowds is a guaranteed way of keeping them occupied while things of real substance are done.”

But are some matters of real substance (such as last week’s ban on entry by residents of seven Muslim-dominated nations) themselves being used to hide even deeper and more significant shifts in power and governance? Steve “I want to bring everything crashing down” Bannon, who has proclaimed himself an enemy of Washington’s political class, is a member of a small cabal (also including Trump, Stephen Miller, Reince Priebus, and Jared Kushner) that appears to be consolidating nearly complete federal governmental power, drafting executive orders, and formulating political strategy—all without paper trail or oversight of any kind. The more outrage and confusion they create, the more effective is their smokescreen for the dismantling of governmental norms and institutions.

There’s no point downplaying the seriousness of what is up. Some commentators are describing it as a coup d’etat in progress; there is definitely the potential for blood in the streets at some point.

Nevertheless, even as political events spiral toward (perhaps intended) chaos, I wish once again, as I’ve done countless times before, to point to a lie even bigger than the ones being served up by the new administration—one that predates the new presidency, but whose deconstruction is essential for understanding the dawning Trumpocene era. I’m referring to a lie that is leading us toward not just political violence but, potentially, much worse. It is an untruth that’s both durable and bipartisan; one that the business community, nearly all professional economists, and politicians around the globe reiterate ceaselessly. It is the lie that human society can continue growing its population and consumption levels indefinitely on our finite planet, and never suffer consequences. Yes, this lie has been debunked periodically, starting decades ago. A discussion about planetary limits erupted into prominence in the 1970s and faded, yet has never really gone away. But now those limits are becoming less and less theoretical, more and more real. I would argue that the emergence of the Trump administration is a symptom of that shift from forecast to actuality.

Consider population. There were one billion of us on Planet Earth in 1800. Now there are 7.5 billion, all needing jobs, housing, food, and clothing. From time immemorial there were natural population checks—disease and famine. Bad things. But during the last century or so we defeated those population checks. Famines became rare and lots of diseases can now be cured. Modern agriculture grows food in astounding quantities. That’s all good (for people anyway—for ecosystems, not so much). But the result is that human population has grown with unprecedented speed.

Some say this is not a problem, because the rate of population growth is slowing: that rate was two percent per year in the 1960s; now it’s one percent. Yet because one percent of 7.5 billion is more than two percent of 3 billion (which was the world population in 1960), the actual number of people we’re now adding annually is the highest ever: over eighty million—the equivalent of Tokyo, New York, Mexico City, and London added together. Much of that population growth is occurring in countries that are already having a hard time taking care of their people. The result? Failed states, political unrest, and rivers of refugees.

Per capita consumption of just about everything also grew during past decades, and political and economic systems came to depend upon economic growth to provide returns on investments, expanding tax revenues, and positive poll numbers for politicians. Nearly all of that consumption growth depended on fossil fuels to provide energy for raw materials extraction, manufacturing, and transport. But fossil fuels are finite and by now we’ve used the best of them. We are not making the transition to alternative energy sources fast enough to avert crisis (if it is even possible for alternative energy sources to maintain current levels of production and transport). At the same time, we have depleted other essential resources, including topsoil, forests, minerals, and fish. As we extract and use resources, we create pollution—including greenhouse gasses, which cause climate change.

Depletion and pollution eventually act as a brake on further economic growth even in the wealthiest nations. Then, as the engine of the economy slows, workers find their incomes leveling off and declining—a phenomenon also related to the globalization of production, which elites have pursued in order to maximize profits.

Declining wages have resulted in the upwelling of anti-immigrant and anti-globalization sentiments among a large swath of the American populace, and those sentiments have in turn served up Donald Trump. Here we are. It’s perfectly understandable that people are angry and want change. Why not vote for a vain huckster who promises to “Make America Great Again”? However, unless we deal with deeper biophysical problems (population, consumption, depletion, and pollution), as well as the policies that elites have used to forestall the effects of economic contraction for themselves (globalization, financialization, automation, a massive increase in debt, and a resulting spike in economic inequality), America certainly won’t be “great again”; instead, we’ll just proceed through the five stages of collapse helpfully identified by Dmitry Orlov.

Rather than coming to grips with our society’s fundamental biophysical contradictions, we have clung to the convenient lies that markets will always provide, and that there are plenty of resources for as many humans as we can ever possibly want to crowd onto this little planet. And if people are struggling, that must be the fault of [insert preferred boogeyman or group here]. No doubt many people will continue adhering to these lies even as the evidence around us increasingly shows that modern industrial society has already entered a trajectory of decline.

While Trump is a symptom of both the end of economic growth and of the denial of that new reality, events didn’t have to flow in his direction. Liberals could have taken up the issues of declining wages and globalization (as Bernie Sanders did) and even immigration reform. For example, Colin Hines, former head of Greenpeace’s International Economics Unit and author of Localization: A Global Manifesto, has just released a new book, Progressive Protectionism, in which he argues that “We must make the progressive case for controlling our borders, and restricting not just migration but the free movement of goods, services and capital where it threatens environment, wellbeing and social cohesion.”

But instead of well-thought out policies tackling the extremely complex issues of global trade, immigration, and living wages, we have hastily written executive orders that upend the lives of innocents. Two teams (liberal and conservative) are lined up on the national playing field, with positions on all significant issues divvied up between them. As the heat of tempers rises, our options are narrowed to choosing which team to cheer for; there is no time to question our own team’s issues. That’s just one of the downsides of increasing political polarization—which Trump is exacerbating dramatically.

Just as Team Trump covers its actions with a smokescreen of controversial falsehoods, our society hides its biggest lie of all—the lie of guaranteed, unending economic growth—behind a camouflage of political controversies. Even in relatively calm times, the über-lie was watertight: almost no one questioned it. Like all lies, it served to divert attention from an unwanted truth—the truth of our collective vulnerability to depletion, pollution, and the law of diminishing returns. Now that truth is more hidden than ever.

Our new government shows nothing but contempt for environmentalists and it plans to exit Paris climate agreement. Denial reigns! Chaos threatens! So why bother bringing up the obscured reality of limits to growth now, when immediate crises demand instant action? It’s objectively too late to restrain population and consumption growth so as to avert what ecologists of the 1970s called a “hard landing.” Now we’ve fully embarked on the age of consequences, and there are fires to put out. Yes, the times have moved on, but the truth is still the truth, and I would argue that it’s only by understanding the biophysical wellsprings of change that can we successfully adapt, and recognize whatever opportunities come our way as the pace of contraction accelerates to the point that decline can no longer successfully be hidden by the elite’s strategies.

Perhaps Donald Trump succeeded because his promises spoke to what civilizations in decline tend to want to hear. It could be argued that the pluralistic, secular, cosmopolitan, tolerant, constitutional democratic nation state is a political arrangement appropriate for a growing economy buoyed by pervasive optimism. (On a scale much smaller than contemporary America, ancient Greece and Rome during their early expansionary periods provided examples of this kind of political-social arrangement). As societies contract, people turn fearful, angry, and pessimistic—and fear, anger, and pessimism fairly dripped from Trump’s inaugural address. In periods of decline, strongmen tend to arise promising to restore past glories and to defeat domestic and foreign enemies. Repressive kleptocracies are the rule rather than the exception.

If that’s what we see developing around us and we want something different, we will have to propose economic, political, and social forms that are appropriate to the biophysical realities increasingly confronting us—and that embody or promote cultural values that we wish to promote or preserve. Look for good historic examples. Imagine new strategies. What program will speak to people’s actual needs and concerns at this moment in history? Promising a return to an economy and way of life that characterized a past moment is pointless, and it may propel demagogues to power. But there is always a range of possible responses to the reality of the present. What’s needed is a new hard-nosed sort of optimism (based on an honest acknowledgment of previously denied truths) as an alternative to the lies of divisive bullies who take advantage of the elites’ failures in order to promote their own patently greedy interests. What that actually means in concrete terms I hope to propose in more detail in future essays.

A Hard-Nosed Optimism

In last week’s essay I used the phrase “hard-nosed optimism” to describe the attitude needed now as “an alternative to the lies of divisive bullies who take advantage of the elites’ failures in order to promote their own patently greedy interests.” This is the optimism Antonio Gramsci probably had in mind when he coined the memorable phrase, “Pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will.”

For those who are paying attention to what’s happening in the world these days, pessimism of the intellect is easy enough to muster. There’s gloom in the air, especially in the United States, where Trump voters responded positively to what was easily the most downbeat pitch from any politician in living memory. In his inaugural address Trump spoke of “American carnage,” and in his campaign speeches and debates he often described the U.S. as virtually a blasted ruin, its cities in a state of advanced decay due to “crime, gangs, and drugs.” Jobs are gone, hope is nearly extinguished; “You walk down the street, you get shot.”

Now, following the election, what is arguably a more reality-based, anger-tinged melancholy has spread to those who voted against Trump. In an interview with Chris Hedges, Kali Akuno, the co-director of Cooperation Jackson and an organizer with the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement in Jackson, Miss, paints about as grim a picture as possible, but one that would likely resonate in the minds of many American progressives:

“All forms of dissent will soon be criminalized. Civil liberties will no longer exist. Corporate exploitation, through the abolition of regulations and laws, will be unimpeded. Global warming will accelerate. A repugnant nationalism, amplified by government propaganda, will promote bigotry and racism. Hate crimes will explode. New wars will be launched or expanded.”

But for those who are really paying attention, the apprehension goes even deeper. The fact is, we are living at history’s greatest inflection point, as I tried to explain in my 2007 book Peak Everything. We today face an extreme ecological crisis (resource depletion, climate change, overpopulation). In addition, there are good reasons to conclude that our financial economy is a house of cards vulnerable to a moderately strong puff of wind. It’s time to brace for impact.

Without pessimism of the intellect, our behaviors are disconnected from reality. If you’re in a ship that’s sinking, it may be possible to act in a way that increases the number of survivors (perhaps only by one). But that requires, first of all, an acknowledgment of the dire situation; denial that your vessel is in trouble merely forecloses possibilities.

But without optimism of the will, intellectual pessimism is paralyzing. What exactly did Gramsci mean by “optimism of the will”? Permit me to speculate a little.

Crisis can often bring out the worst qualities in people. Tumult creates opportunities for . . . well, opportunists—bullies and hucksters. We have an example readily at hand: someone of Donald Trump’s character probably could not have arisen in American politics during a period of generally growing affluence such as prevailed in the 20th century (yes, we endured some dullards and crooks—but no one even approaching Trump’s level of pugnacious mendacity). But while bullies and hucksters can gain power and sow discord, they can’t be looked to as agents for improvement of our long-term survival prospects. For that, entirely different qualities of character are required.

As global industrial civilization fragments, persistence of the best of what we humans are and have achieved will require us to build resilient, enduring communities—ones with high internal levels of mutual trust, and that are capable of adapting quickly to changing conditions and responding effectively to a range of threats. Such communities arise and sustain themselves only by nurturing and prizing certain qualities of character on the part of their members.

The people who are most likely to be of use in such communities are those who exhibit old-fashioned virtues, including honesty, bravery, self-control, cheerfulness, humility, and generosity. The ability to amuse and entertain oneself and others will be a welcome bonus; likewise the ability to speak convincingly, and the willingness both to endure discomfort and to find satisfaction in small things. I think qualities like these may start to get at what Gramsci meant by “optimism of the will.”

None of us scores 100 on the character test. In fact, writing about noble qualities of character is uncomfortable, because doing so inevitably invites investigation into the character of the writer—and I’m certainly not proposing to set myself up as an example. All I can say is, I’m trying (not hard enough, I’m sure some would say). Nevertheless the subject of character seems unavoidable.

Initially, character is formed by early childhood experiences, by culture, and perhaps also by heredity. Consumer culture reliably produces generations of self-absorbed whiners, and social media don’t seem to be helping much with that. But even with such excuses readily at hand, no competent adult can abdicate the responsibility for character building, which is an ongoing and cumulative task.

Indigenous people knew all about this. They had to rely on direct daily interactions with one another for nearly everything, and everyone knew that habitual complaining, lying, and boasting could eventually get you ostracized—effectively a death sentence. Reading accounts by early European explorers, or by later first-contact field anthropologists, one cannot help but be struck by the degree to which people in the simplest societies held themselves and one another to a high standard of speech and behavior.

Modern economies appear to run less on character, more on energy, resources, investment, debt, and innovation. But in the world that’s coming, who we are may once again matter more than what we have.

Notice I haven’t mentioned technology much in this essay. Most future gazing, whether of the utopian or dystopian variety, focuses on tools and what they can do for us. If civilization gets downsized in the next few decades, then knowing how to build and operate low-tech devices for meeting human needs will undoubtedly aid with survival. But really effective preparation for what’s coming may best begin not with our choice of gadgetry, but with ourselves.

Unless we are able to build human cultures that truly deserve to survive, what’s the point of survival? And such cultures must be comprised of, and sustained by, people who hold quality of character as the highest good.

If it takes a Donald Trump to remind us of this ancient truth, then at least he will have done us that service.

Protest sign photo credit: arindambanerjee/shutterstock.com

![[Power book cover]](https://richardheinberg.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/cover_POWERcatalog-proof_300x450.jpg)