MuseLetter #320 / Janary 2019 by Richard Heinberg

Download printable PDF version

This first Museletter of 2019 brings you two articles. The first examines the challenge and potential benefits of breaking our economic growth addiction. The second is a tongue-in-cheek take on the age of the automobile.

Sooner or Later, We Have to Stop Economic Growth — and We’ll Be Better for it

Both the U.S. economy and the global economy have expanded dramatically in the past century, as have life expectancies and material progress. Economists raised in this period of plenty assume that growth is good, necessary even, and should continue forever and ever without end, amen. Growth delivers jobs, returns on investment and higher tax revenues. What’s not to like? We’ve gotten so accustomed to growth that governments, corporations and banks now depend on it. It’s no exaggeration to say that we’re collectively addicted to growth.

The trouble is, a bigger economy uses more stuff than a smaller one, and we happen to live on a finite planet. So, an end to growth is inevitable. Ending growth is also desirable if we want to leave some stuff (minerals, forests, biodiversity and stable climate) for our kids and their kids. Further, if growth is meant to have anything to do with increasing quality of life, there is plenty of evidence to suggest it has passed the point of diminishing returns: Even though the U.S. economy is 5.5 times bigger now than it was in 1960 (in terms of real GDP), America is losing ground on its happiness index.

So how do we stop growth without making life miserable — and maybe even making it better?

To start with, there are two strategies that many people already agree on. We should substitute good consumption for bad, for example using renewable energy instead of fossil fuels. And we should use stuff more efficiently — making products that last longer and then repairing and recycling them instead of tossing them in a landfill. The reason these strategies are uncontroversial is that they reduce growth’s environmental damage without impinging on growth itself.

But renewable energy technology still requires materials (aluminum, glass, silicon and copper for solar panels; concrete, steel, copper and neodymium for wind turbines). And efficiency has limits. For example, we can reduce the time required to send a message to nearly zero, but from then on improvements are infinitesimal. In other words, substitution and efficiency are good, but they’re not sufficient. Even if we somehow arrive at a near-virtual economy, if it is growing we’ll still use more stuff, and the result will be pollution and resource depletion. Sooner or later, we have to do away with growth directly.

Getting Off Growth

If we’ve built our institutions to depend on growth, doesn’t that imply social pain and chaos if we go cold turkey? Perhaps. Getting off growth without a lot of needless disruption will require coordinated systemic changes, and those in turn will need nearly everyone’s buy-in. Policymakers will have to be transparent with regard to their actions, and citizens will want reliable information and incentives. Success will depend on minimizing pain and maximizing benefit.

The main key will be to focus on increasing equality. During the century of expansion, growth produced winners and losers, but many people tolerated economic inequality because they believed (usually mistakenly) that they’d one day get their share of the growth economy. During economic contraction, the best way to make the situation tolerable to a majority of people will be to increase equality. From a social standpoint, equality will serve as a substitute for growth. Policies to achieve equity are already widely discussed, and include full, guaranteed employment; a guaranteed minimum income; progressive taxation; and a maximum income.

Meanwhile we could begin to boost quality of life simply by tracking it more explicitly: instead of focusing government policy on boosting GDP (the total dollar value of all goods and services produced domestically), why not aim to increase Gross National Happiness — as measured by a selected group of social indicators?

These are ways to make economic shrinkage palatable; but how would policymakers actually go about putting the brakes on growth?

One tactic would be to implement a shorter workweek. If people are working less, the economy will slow down — and meanwhile, everyone will have more time for family, rest and cultural activities.

We could also de-financialize the economy, discouraging wasteful speculation with a financial transaction tax and a 100 percent reserve requirement for banks.

Stabilizing population levels (by incentivizing small families and offering free reproductive health care) would make it easier to achieve equity and would also cap the numbers of both producers and consumers.

Caps should also be placed on resource extraction and pollution. Start with fossil fuels: annually declining caps on coal, oil and gas extraction would reduce energy use while protecting the climate.

Cooperative Conservatism

Altogether, reining in growth would come with a raft of environmental benefits. Carbon emissions would decline; resources ranging from forests to fish to topsoil would be preserved for future generations; and space would be left for other creatures, protecting the diversity of life on our precious planet. And these environmental benefits would quickly accrue to people, making life more beautiful, easy and happy for everyone.

Engineering a happy conclusion to the growth binge of the past century might be challenging. But it’s not impossible.

Granted, we’re talking about an unprecedented, coordinated economic shift that would require political will and courage. The result might be hard to pigeonhole in the capitalist-socialist terms of reference with which most of us are familiar. Perhaps we could think of it as cooperative conservatism (since its goal would be to conserve nature while maximizing mutual aid). It would require a lot of creative thinking on everyone’s part.

Sound difficult? Here’s the thing: ultimately, it’s not optional. The end of growth will come one day, perhaps very soon, whether we’re ready or not. If we plan for and manage it, we could well wind up with greater well-being. If we don’t, we could find ourselves like Wile E. Coyote plunging off a cliff. Engineering a happy conclusion to the growth binge of the past century might be challenging. But it’s not impossible; whereas what we’re currently trying to do — maintain perpetual growth of the economy on a finite planet — most assuredly is.

Originally published at Ensia.

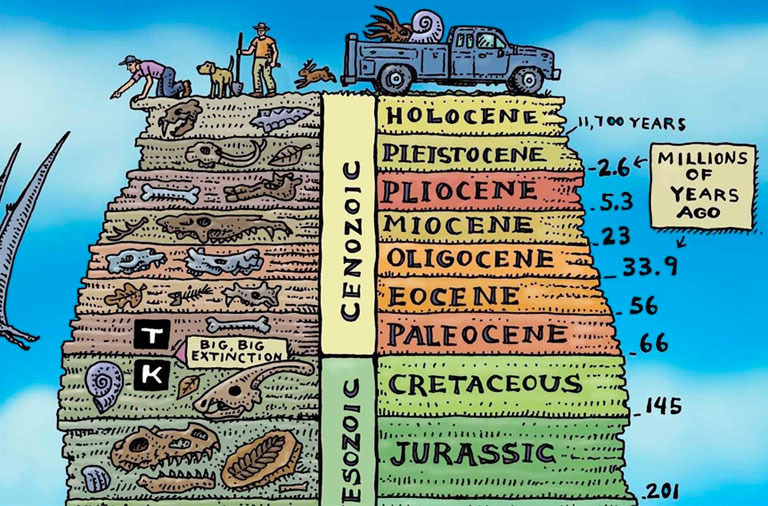

Living in the Concretaceous Period

Scientists long ago determined that Earth had entered the Anthropocene period, based on a determination that humans were altering fundamental planetary parameters such as biodiversity and the chemistry of the atmosphere and oceans to the degree that it warranted an entirely new geological designation. Following another millennium of observation and analysis, skilled observers now tend to divide the Anthropocene into brief but distinct phases, including the Concretaceous, the Hellocene, and the current Depletozoic—which began centuries ago and appears likely to persist until the next awful thing happens.

While biologists have long agreed that humans are the dominant lifeform of the Anthropocene, some geologists now argue that, during the pivotal Concretaceous phase, it was the automobile that served as the true apex species. It was for the sake of automobiles that concrete—the signature rock stratum of the Concretaceous—was laid down over millions of square kilometers of landscape. The automobile served as a kind of exoskeleton for Concretaceous humans, as well as a status symbol, and it was for the powering of automobiles that millions of years’ worth of ancient sunlight, stored in the form of petroleum, was wrenched from the ground and combusted—thus altering the climate and triggering the swarm of events that led to the second phase of the Anthropocene, the Hellocene.

This latter observation has led some historians to explore the evolution of the automobile, from the primitive Stutzes and Locomobiles that rolled the primordial roads of the early Concreteaceous, all the way to the sleek Teslas and other electric cars that began to proliferate just as the swiftly intensifying events of the brief Hellocene brought the Concretaceous to a hot, chaotic end. At the thin Concretaceous-Hellocene boundary, there is some evidence to suggest the nascent evolution of driverless automobiles—which might eventually have made humans themselves obsolete, had not the catastrophic dawning of the Hellocene marked the extinction of the automobile itself, as well as the disappearance of millions of plant and animal species and the near-extinction of humans.

So many puzzles remain. Why were humans in the Concretaceous phase unable logically to foresee the inevitable consequences of their collective behavior? Why were humans so fascinated by automobiles that they were willing to imperil so many other creatures? What was the function of the small rectangular boxes that late Concretaceous humans seemed to carry with them at all times? Were they merely generic votive objects, or did they enable communication with distant spirits, as legend insists? Perhaps we will never know. Ongoing research can still teach us much about the strange ways of the powerful but doomed people of the early Anthropocene.

Skyscrapers image by Sean Pollock on Unsplash

Geologic Eras by Ray Troll: Ray Troll

![[Power book cover]](https://richardheinberg.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/cover_POWERcatalog-proof_300x450.jpg)