MuseLetter #288 / May 2016 by Richard Heinberg

Download printable PDF version here (PDF, 292 KB)

First up in this month’s Museletter is a satirical take on Donald Trump’s stance on climate change – a humorous slant on a serious matter. Also included is an excerpt from a chapter I wrote on energy constraints to urbanization for the new book from The Worldwatch Institute, Can a City Be Sustainable? (State of the World).

Millions of Americans Now Claim Donald Trump Does Not Exist

On May 13 the American news media reported that presumptive Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump had recruited U.S. Republican Congressman Kevin Cramer of North Dakota—a major oil drilling state—to help him draft his energy policy. Cramer has said he does not believe in human-caused climate change and that he therefore opposes efforts by the Obama administration to regulate greenhouse gas emissions.

Perhaps partly in response to Trump’s and Cramer’s climate views, surveys now suggest that millions of Americans doubt Donald Trump’s existence. On its face, this belief appears to fly in the face of abundant evidence—including Trump’s image on television and in newspapers, accounts and recordings of his speeches, and large buildings with his name emblazoned on them. Nevertheless, polls show the “Trump doesn’t exist” crowd is growing in numbers and in confidence.

Some Trump deniers appear to have adopted their views for strategic reasons. Mary Hartford of Nashville, Tennessee argues that, “If evidence of climate change can be denied, so can evidence of Trump’s existence. I believe this is a matter of personal choice. I’ve heard that several actual scientists take this view, so it’s fair to say there is no scientific consensus that Trump is a real entity. Until the matter is settled to my satisfaction, the question should be left open.” Hartford insists, “We choose our own reality. Trump has chosen to inhabit a reality in which climate change does not exist. We choose a reality in which Trump does not exist. It’s just as valid.”

Others are more genuinely skeptical of Donald Trump’s reality and say that the reputed evidence of his existence is due to a giant conspiracy. Asked why such evidence doesn’t convince him, Ima D. Nyer, a spokesman for the organization #ThereIsNoDonald told this reporter, “All of that material can be and has been doctored. Research has shown that none of those buildings with Trump’s name on them is actually owned by a real person named Donald Trump. And the birth certificate for Trump that’s on record is obviously forged. What else are we to conclude but that it’s all an elaborate hoax? Whether there ever was a person corresponding to the mythical Donald is an open question, but we’re convinced that the candidate going by that name is nothing but a lot of video images of an actor photoshopped over a series of backdrops including rallies, debates, and interviews.”

There may eventually be practical fallout from the “Is Trump Real?” debate. Doubters insist that school children should be taught that Trump’s existence is “controversial,” and that inclusion of the candidate’s name on ballots across the country should be subject to legal challenges.

When asked why anyone would go to the trouble to create such an elaborate fraud, Nyer of #ThereIsNoDonald said, “The punditocracy just loves this illusory figure it has created. Their fictitious Trump has sold more newspapers and has generated more advertising revenue than any other person or event in the past decade. Inventing Donald Trump was the smartest idea they ever had.”

Even some religious groups doubt Trump’s existence. Carl McCarthy of the Southwest Synod of the Evangelical Brotherhood of Seekers says that a kind and loving God would never send someone like Donald Trump into the world to sow so much division and enmity. “Given the choice,” says McCarthy, “I’d prefer to believe that Trump is a figment of humanity’s collective imagination.”

Asked to speculate which (climate change or Trump), if real, would do the greater amount of harm to the Earth and its people, McCarthy chose not to answer the question directly. Instead he replied, “Believing that climate change exists and that Donald Trump also exists is just too much for my fragile psyche. The implications are just too depressing for words. One of them had to go, and I chose the one for which the evidence is flimsier—Trump, obviously.”

Possible Energy Constraints to Further Urbanization

The following is an excerpt from a chapter by Richard Heinberg which is included the new book Can a City Be Sustainable? (State of the World) by The Worldwatch Institute.

The last few decades have seen dramatic urban expansion as a result of both global population growth and the influx of rural migrants to cities. Most futurists assume that this trend will continue throughout the current century, and many environmentalists welcome the prospect of urbanization because cities seem to impose lower environmental costs, per person, for a given standard of living.

How long can the trend toward urbanization continue in the face of this century’s energy and climate constraints?

Industrial civilization—the biggest energy extravaganza in human history—arose due to the historically anomalous advent of fossil fuels, with their ability to deliver dense, portable, easily storable, and cheap energy in unprecedented quantities. Fossil fuels replaced most human labor in agricultural production and also provided faster and more-efficient means of bringing distant resources to urban hubs.

But our current fossil fuel-based energy regime faces two serious challenges: depletion of the “low-hanging fruit” of global petroleum supplies, and the need to reduce carbon emissions to avert catastrophic climate change.

Efforts to replace coal and natural gas with wind and solar energy have begun in the electricity sector. However, the challenge of a full transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources is more daunting when it comes to petroleum. Crude oil and products derived from it account for nearly two-thirds of global transport fuels.

The two economic sectors most vulnerable to oil supply limits (imposed either by depletion or by efforts to mitigate climate change) are agriculture and transport, and both are pivotal to continued urbanization.

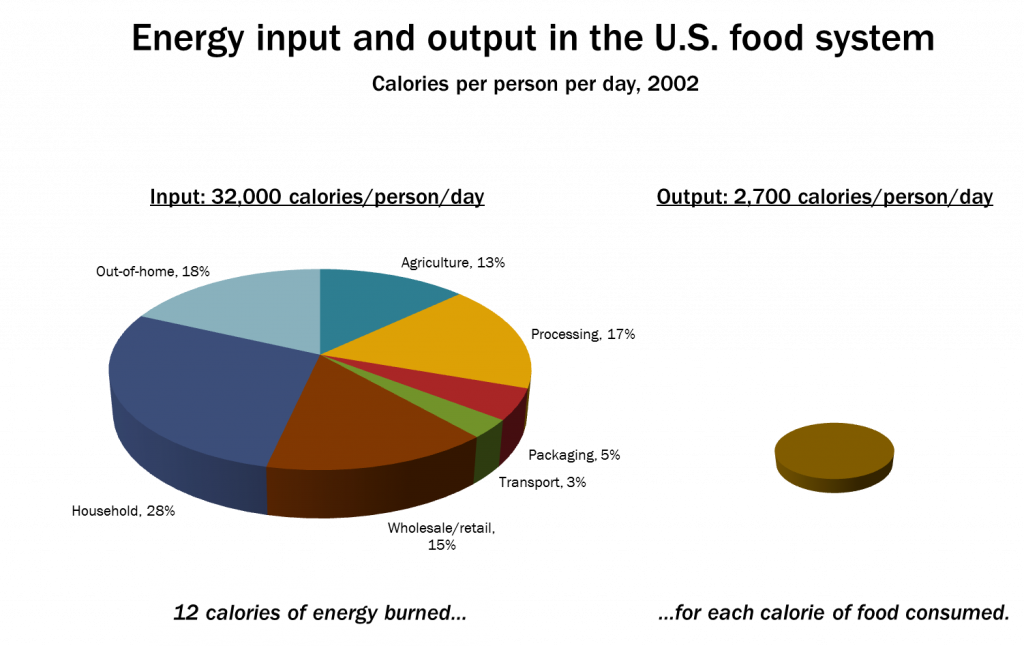

Although agriculture was the primary source of energy for pre-industrial societies, industrial agriculture is a net consumer of energy. The Green Revolution, which more than doubled cereal production in developing countries between the years 1961 and 1985, succeeded by vastly increasing inputs—nitrogen fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides—all made from fossil fuels. The U.S. food system, which served as a model for the Green Revolution, consumes approximately 12 calories of energy (mostly from fossil fuels) for every food calorie delivered to the final consumer.

Energy Input and Output in the U.S. Food System, 2002

Ways to reduce fossil fuel inputs to food systems include the use of farm machinery powered by renewable electricity or farm-produced biofuels; the localization of food systems to reduce transport (perhaps entailing vertical urban agriculture); the adoption of organic and ecological production practices to reduce the need for nitrogen fertilizer, pesticides, and herbicides; and an overall reduction in the consumption of highly processed foods.

If smaller-scale organic production cannot produce high-enough yields, or if the transition is hampered by a failure to train farmers adequately or quickly enough or to undertake land reforms required, then the consequences of a significant involuntary reduction in the availability of oil to food systems would be severe. Crucially, even if small-scale organic practices did prove sufficiently productive, more agricultural labor would be needed, perhaps encouraging (or requiring) many people to move back to the countryside. It is possible to imagine methods by which this “re-ruralization” could be accomplished that are either progressive in nature (ecological farm co-ops, for instance) or regressive (a new serfdom).

Cities depend overwhelmingly on powered transport for obtaining raw materials for manufacturing (nearly all of which occurs in or near cities); for importing and exporting manufactured goods; for moving people to and from home, work, shopping, school, and cultural events; for importing food; and for exporting wastes of various kinds.

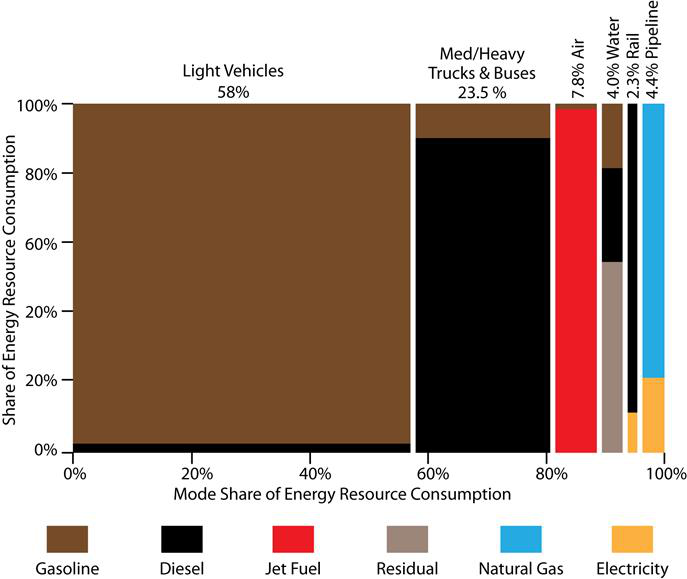

In industrialized countries, the lion’s share of oil consumption in the transport sector occurs in private automobiles. Trucking and aviation vie for second place in most countries, with rail and public transportation assuming more modest roles. However, the fuel efficiency of moving 1 kilogram of material a distance of 1 kilometer runs more or less in the reverse order.

One response to the declining availability of petroleum is to discourage low-occupancy car use and air travel while encouraging the use of walking, bicycling, and public transit for short distances and rail for medium and long distances. Making such a shift requires significant investments and changes to land-use and transportation policies, which inevitably are politically contested. But, as many cities around the world have been discovering, the results often are quite popular and beneficial.

Overall, cities may need to adapt to more-localized raw materials sourcing, manufacturing, and waste disposal.

In a world with less liquid transport fuel, it is hard to see how cities could continue growing as they have in recent decades.

Prior to the fossil-fueled Industrial Revolution, the share of the global population that lived in cities was small—less than 10 percent. Today, just over half of humanity lives in cities. At some stage, the trend toward urbanization will taper off or even reverse itself. It is impossible to know how close we are to that tipping point, but it could well occur during this century, and a decline in available energy is likely to be the key driving factor.

Analogous historic moments have been associated with the collapse of complex societies. Civilization is defined, literally, by city dwelling (civis, the Latin root of the word civilization, means “city”). Urban living historically has brought with it social stratification and full-time division of labor. As civilizations expand, they urbanize; when they fail, cities empty out and people return to subsistence agriculture or foraging. The process of collapse typically entails massive mortality.

As ancient civilizations crumbled, absent sound leadership from elites, people responded by creating new, simpler social and economic arrangements that required smaller energy investments. We can see the faint beginnings of similar trends today in the “sharing economy,” in organizations of idealistic young organic farmers, and in Transition initiatives. Although the 1970s “back-to-the-land” movement (which coincided with historic energy crises) largely fizzled, perhaps due to cheap oil flowing from the North Sea and Alaska during the 1980s and 1990s, we may be on the cusp of similar, more widespread, and possibly more desperate trends today.

BUY THE BOOK – Order your copy now using the discount code 4SOTW

From Can a City Be Sustainable? (State of the World) by The Worldwatch Institute. Copyright © 2016 Worldwatch Institute. Reproduced by permission of Island Press, Washington, DC.

![[Power book cover]](https://richardheinberg.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/cover_POWERcatalog-proof_300x450.jpg)