MuseLetter #316 / September 2018 by Richard Heinberg

Download printable PDF version here (PDF, 160 KB)

Society as Ecosystem in a Time of Collapse, Part III

This month’s Museletter is the concluding part of my 3-part essay using predation as a metaphor to unpack power relations in human societies. Read Part I, read Part II.

6. “Disease organisms” (revolutionaries), “parasites” (criminals), and “immune systems” (law and punishment) in times of growth and release

In his brilliant 1976 book Plagues and Peoples, historian William H. McNeill explored how infectious disease has shaped human societies through the ages. A remarkable paragraph on page 84 of the Anchor paperback edition has stayed with me for several decades and partly inspired this essay:

Very early in civilized history, successful raiders became conquerors, i.e., learned how to rob agriculturalists in such a way as to take from them some but not all of the harvest. By trial and error a balance could and did arise, whereby cultivators could survive such predation by producing more grain and other crops than were needed for their own maintenance. Such surpluses may be viewed as the antibodies appropriate to human macroparasitism. A successful government immunizes those who pay rent and taxes against catastrophic raids and foreign invasion in the same way that a low-grade infection can immunize its host against lethally disastrous disease invasion. Disease immunity arises by stimulating the formation of antibodies and raising other physiological defenses to a heightened level of activity; governments improve immunity to foreign macroparasitism by stimulating surplus production of food and raw materials sufficient to support specialists in violence in suitably large numbers and with appropriate weaponry. Both defense reactions constitute burdens on the host populations, but a burden less onerous than periodic exposure to sudden lethal disaster.

At the risk of over-quoting, I will reproduce McNeill’s next paragraph as well. He’s on a roll here, and the explanatory firepower of these passages is measurable in megatons. These are insights that would later help win a Pulitzer Prize for Jared Diamond’s book Guns, Germs, and Steel. Remember: the context of his discussion is the role of disease organisms in the evolution of human societies.

The result of establishing successful governments is to create a vastly more formidable human society vis-à-vis other human communities. Specialists in violence can scarcely fail to prevail against men who have to spend most of their time producing or finding food. And as we shall soon see, a suitably diseased society, in which endemic forms of viral and bacterial infection continually provoke antibody formation by invading susceptible individuals unceasingly, is also vastly more formidable from an epidemiological point of view vis-à-vis simpler and healthier human societies. Macroparasitism leading to the development of powerful military and political organization therefore has its counterpart in the biological defenses human populations create when exposed to the microparasitism of bacteria and viruses. In other words, warfare and disease are connected by more than rhetoric and the pestilences that have so often marched with and in the wake of armies.

Now, having stood and cheered for McNeill’s metaphoric usage of “parasitism,” I’m going to do something that I hope will not be too confusing. Take a deep breath and bear with me.

McNeill uses the term “macroparasitism” in much the same way I have been using “predation.” I have no desire to quibble: his metaphorical framing serves his purposes well and is revelatory for readers. However, it seems to me that a somewhat different framing can be just as helpful— “parasitism” referring metaphorically to crime; “disease microbes” to rebels, revolutionaries, terrorists, and invading barbarians; and “immune system” to laws, enforcement, and punishment.

From the perspective of lower classes, elites often appear “parasitic” (as Marx’s followers insisted; as Michael Hudson suggests in his book cited previously, referring to today’s financial elite; and as McNeill does above). I would argue that this usage is not incorrect, but that it can be helpfully supplemented with another perspective. Elite classes are integral to complex societies. However, actual parasites are alien organisms relative to their hosts. The criminal, like a parasite, exists apart from the corpus of the state; his or her behavior is regarded as “antisocial” (a partial exception occurs in the case of political corruption, which I’ll discuss below).

Parasitism and infectious disease are closely related: disease-causing microbes are by definition parasitic; however, large parasites like intestinal worms and mosquitoes are seldom described as disease organisms. Host organisms typically co-evolve with their parasites; as a result, the latter tend to weaken but seldom kill their hosts. Infectious diseases, however—especially in cases where no host defenses have co-evolved—can be fatal. Similarly, crime is present in all complex societies and is seldom fatal to them. Revolution or invasion, though, can indeed be fatal to the body politic in some instances.

The case for criminality as “parasitism” is relatively easy to make for property crimes, which drain wealth (“lifeblood”) from society; however, not all criminal acts appear to be overtly “parasitic”: crimes of passion, including murder motivated by jealousy or rage, might seem to poorly fit our metaphor. However, as anthropologist Stanley Diamond noted in his 1974 book In Search of the Primitive, early civilizations regarded murder and suicide as property crimes, since they deprived the state of its subjects. Citing examples from many cultures, Diamond argued that concepts of property, law, and crime emerged and evolved together. As pre-state customs for resolution of disputes evolved into law (often via census-tax-conscription systems), specialists in charge of enforcement, representation, adjudication, confinement, and punishment also appeared.

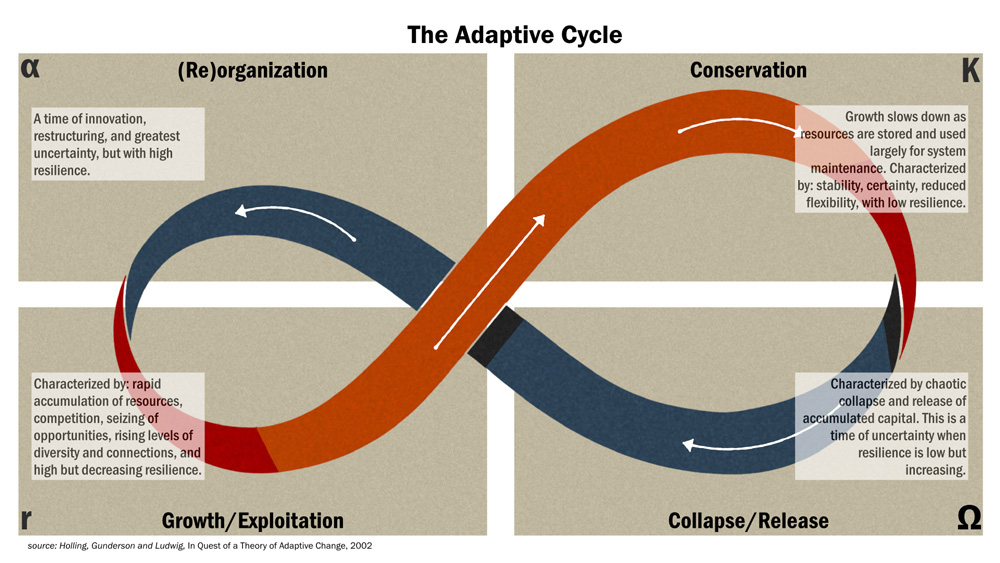

Crime is always present in complex societies, just as all higher-order organisms are subject to parasites. But once a society is weakened, as it is when it approaches the release phase of an adaptive cycle, it can be overwhelmed especially by “microparasites” analogous to disease microbes—rebels, revolutionaries, terrorists, or invaders. This is why societies tend to prescribe particularly harsh punishments for anti-state crimes.

We could liken law and its enforcement to an immune system: it works to ward off “parasites” of all kinds. Legal systems have resulted in a dramatic decline of interpersonal violence during the past few thousand years of civilized history. And particularly within democracies, some laws serve to shield citizens against the abuse of state power, through the assignment and protection of rights. The legal system works to the benefit of the society as a whole, even if some members benefit disproportionately while others are crushed.

However, legal and political systems can themselves become corrupted—that is, taken over by criminals. Political and police corruption could be seen metaphorically as an “auto-immune disorder” in which the defenses of the body politic turn against healthy “cells.” Such corruption may again be symptomatic of the approach of the release phase of a societal adaptive cycle. At such times, citizens may invent or revive ways of resolving conflict without state intervention (efforts running the gamut from vigilantism to restorative justice). In a release phase, the legal and political systems come to be perceived as rigged. Disputes arise about the purpose and efficacy of law, enforcement, and punishment. In the extreme instance, criminals become political leaders and leaders become criminals.

7. Politics: democracy and authoritarianism in the release phase

As I’ve discussed at greater length in another recent essay, it is probably wrong to think of democracy as a recent invention, since many pre-agricultural societies tended to be highly egalitarian. In contrast, most early states appear to have been ruled by kings and pharaohs. Several millennia after the agricultural revolution (which began roughly 10,000 years ago), notably in Greece, a limited form of democracy emerged as a means of regaining some of the personal freedoms and participation in leadership that had been mostly lost with the advent of cities, states, and kings.

During the past two centuries, democracies have become much more common than ever before, especially in European nations and their former colonies. This trend is often attributed to “enlightenment” and a popular yearning for liberty. However, it is also possible that the vast production of wealth from colonialism and fossil fuels provoked rising expectations for wider distribution of both economic and political power—initially, in America, among the minority population of European-American males with property. From the mid-19th century onward, the threat of Marxist revolution may also have helped persuade the “predator” classes that it was in their interest to give the general populace at least a semblance of participation in governance.

If these speculations are at least partly correct, then we might also hypothesize that democracy tends to be favored most in the growth and conservation phases of a civilization’s adaptive cycle (as was the case of ancient Rome, whose Republic endured for roughly four centuries, but gradually withered following the creation of the Empire in 27 BCE). When there’s plenty to go around, the real rulers—who may benefit from a degree of anonymity—can afford to be relatively generous with the public, while sometimes cultivating figurehead and puppet leaders who faithfully serve elite interests even though they appear to arise from, and represent, the people. Just as prey participate (mostly passively) in their own domestication, suitably sated and propagandized middle and working classes may help ease the occasional tensions of elite domination.

But as a release phase in the cycle approaches, there is less of a surplus available for redistribution, and the “predator” classes are likely to be in less of a mood to share. As long as there is surplus, the “prey” classes can be mollified with regard to the disproportionate amounts of wealth being arrogated by the “predator” class, because the “prey’s” well-being is also improving (though less) and because of opportunity for class mobility (real or perceived) offers the hope that they, too, could become part of the “predator” class. But when surplus evaporates, the effectiveness of these mechanisms of appeasement fades. As inequality grows, so do social strains. Management of mass perception (increasingly focused on assigning blame) becomes an increasing preoccupation of politicians, political commentators, and strategists. At the same time, elites are likely to come into greater conflict with one another. As public relations specialists working for elite interests employ clashing narratives to spin events, “prey” classes are more likely to be drawn toward political extremes.

Such a moment provides an opening for powerful personalities who promise to vanquish villains and return the nation to a condition of lost stability, moral uprightness, and magnificence. Popular enthusiasm for checks and balances between governmental departments, fair elections, and respectful discourse withers in favor of scapegoating, dirty tricks, and winning-by-any-means. The niceties of democracy can be dispensed with, if only the Great Leader can deliver!

The strong man may be a member of the “predator” class—a metaphoric “alpha wolf” whose main goal is to more effectively fleece the “sheep.” On the other hand, depending on social circumstances, a release moment may provide the opening for a true populist—a member of the “prey” classes who is persuasively intent on leveling power and wealth within the nation. But, given chaotic conditions, even in that case the formal operations of democracy may still be held in abeyance.

Unfortunately for tyrants, the release phase of a societal adaptive cycle is an awful time to be in charge. The former golden age cannot be restored. Someone must eventually be held to account, and the authoritarian leader is the most visible culprit. But overthrowing him (or her?) does little to right the ship of state. The inexorable process of creative destruction must work its way through until there is the ecological basis for a new phase of reorganization.

8. Summary: The usefulness (and limits) of the “predator-prey” metaphor

Is the “predator-prey” frame helpful? What have we learned that’s relevant to our present global milieu?

Both conflict and integrationist explanations for the evolution of societal complexity could be said to be applicable, though each seems a better fit for certain times, places, and practices. In describing raiding, conquest, colonialism, and slavery, conflict (“predator-prey”) theory fits the facts well and offers insights. In the case of a modern industrial state with welfare programs and universal healthcare, it is easy to argue that everyone benefits by cooperating to enable the creation and maintenance of such a wealthy and formidable society, even if some benefit more than others. However, that benefit is contingent on the society’s ability to sustain itself in the long term. If it is operating in a way that undermines its own ecological foundations, all will eventually suffer.

The contradiction between conflict and integration theories is somewhat resolved in the “domestication” metaphor. Most members of society benefit to some degree from the cooperation between “predator” and “prey” implied in the process of human-on-human “domestication” (though this could hardly be argued to be the case for slavery and its aftermath—which may continue for generations). But whatever mutual benefit accrues is subject to negotiation, and also to the phases of the adaptive cycle.

In adopting the “predator-prey” frame, I have leaned toward an interpretation of human history that is conflict-based, even though complex society is inherently a cooperative structure. Perhaps the integrationist view is more useful in understanding the growth phase of the societal adaptive cycle. As the release phase approaches, the social contract may fail, and “predator-prey” relations may become more naked and severe. If and when this happens, conflict theory may be more applicable and revelatory. However, in finding our path through the release phase and toward a phase of reorganization, it may be essential to find ways to cooperate that minimize or exclude “predation.”

Perhaps seeing the class and power dynamics of society through the lens of “predation” can highlight the machinery of inequality and exploitation, helping us avoid being “preyed upon” and “preying upon” others, and inspiring us to help loosen the bonds of “domestication” that harness our fellow citizens. Yet we may also become inspired to think about ways of building forms of social complexity that do not depend upon warfare and “predation.” Perhaps this course of cultural evolution would constitute the metaphoric equivalent of becoming a species of primary consumers—i.e., vegetarians. Though I personally have maintained a vegetarian diet for several decades, I harbor no illusion that the rest of humanity is likely to adopt a similar lifestyle anytime soon (although doing so would dramatically reduce our impact upon climate and land use). Nevertheless, both metaphoric and literal vegetarianism can be pursued in degrees. As I’ve stressed in this essay, even in complex and stratified societies levels of inequality in power and wealth are highly variable. The pursuit of more cooperative and less exploitative social structures can take many forms—experiments with innovative democratic institutions (ways of increasing voter participation, direct representation, ranked choice voting, etc.), re-commoning, bioregionalism, and more.

Another potential benefit from the framing employed in this essay is the possibility of increasing awareness of the nature of our collective current global predicament. As we have seen, human-on-human and human-on-nature “predation” are ultimately self-limiting, and there is evidence to suggest that we are reaching certain limits. We appear to be on the cusp of seismic shifts in the global ecosystem, and in human financial, social, and political systems. This means we are also at a time when new thinking and ways of doing things are required, and may have a chance of overturning well-established norms.

As Peter Turchin documents in Ultrasociety, we humans were already on a track toward higher levels of social complexity and less interpersonal violence prior to the fossil-fueled industrial age. As the carbon-fed growth bubble pops there is the prospect for a great unraveling, accompanied by a significant rise in violence, at least in the short term; but there is also the possibility that the longer-term trend Turchin points to will eventually reassert itself. Perhaps discovering how cooperation and complexity are possible without social “predation” will constitute our next evolutionary project.

Feature image: Russian Cossacks raid a French village during the Napoleonic wars. Painting by Peter Heinrich Lambert of Hess. Source.

![[Power book cover]](https://richardheinberg.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/cover_POWERcatalog-proof_300x450.jpg)