MuseLetter #378 / September 2024 by Richard Heinberg

Download printable PDF version

Us vs. them: Understanding the roots of political polarization and what you can do about it

July 13, 2024, Butler, PA: Former president and current presidential candidate Donald Trump survives an assassination attempt at an election rally; the gunman and a bystander are killed, with two others critically wounded.

May 16, 2024, Handlova, Slovakia: Slovakian Prime Minister Robert Fico is seriously wounded in a politically motivated assassination attempt.

May 3, 2024, Dresden, Germany: Matthias Ecke, a leading socialist member of the European Parliament, is brutally attacked and seriously injured while putting up campaign posters. This follows other recent physical assaults on German politicians.

January 8, 2024, Guayaquil, Ecuador: masked men invade the set of a live broadcast on a public television channel waving guns and explosives; the president issues a decree declaring that the country has entered an “internal armed conflict.”

There are nearly 200 countries in the world, and there’s seemingly always political conflict in at least one of them. So, a few examples don’t necessarily indicate a general trend. However, experts say political violence is tied to polarization—the divergence of political attitudes away from the center and toward ideological extremes. And poll-based studies show that politics are becoming more polarized worldwide.

One measure of polarization is the annual Edelman Trust Barometer; in its most recent poll of more than 32,000 respondents across 28 countries, most respondents (53 percent) said their countries are more divided today than in the past.

The U.S., Colombia, South Africa, Argentina, Spain, and Sweden are considered severely polarized, according to the Edelman data. Brazil, Mexico, France, the U.K., Japan, Italy, Germany, and the Netherlands are in danger of severe polarization.

In this article, we’ll explore why societies become polarized. We’ll unpack the dangers of polarization and the ways it tears societies apart. We’ll trace the causes and history of polarization in the U.S. And we’ll see what can be done to reverse polarization. In a separate article, I’ll discuss the global factors that make the current era especially polarizing, and explore the question of whether democracy can survive these trying circumstances.

Polarization Drivers: The Findings of Sociologists and Historians

The most comprehensive recent book-length discussion of political polarization worldwide is Democracies Divided: The Global Challenge of Political Polarization, by Thomas Carothers and Andrew O’Donohue. A certain amount of polarization is normal and healthy in a modern democracy, in the authors’ view. Extreme polarization occurs when the usual spectrum of political opinion coalesces into just two primary ideologies that harden into identities adopted by opposing blocs of people, each regarding the other with contempt and fear. Extreme polarization is also typically sustained beyond a specific election, and it “reverberates throughout the society as whole, poisoning everyday interactions and relationships.”

According to Carothers and O’Donohue, the drivers of extreme polarization include religion, tribal or ethnic identity, political ideology, economic transformation, changes in the media landscape, and the design of political systems (for example, two-party systems are more prone to polarization than systems with three or more parties).

These drivers can set the stage for the rise of polarizing leaders, who demonize a political or ethnic group in order to build a base of highly motivated followers. Recent examples include Narendra Modi in India and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in Turkey; both gained electoral success by inflaming and entrenching divisions in their societies. Polarizing leaders often crash against political and legal guardrails, such as by prosecuting political rivals, attacking the judiciary, banning or limiting opposition media, and passing laws to criminalize dissent (Modi’s chief political rival was prosecuted and imprisoned, while Erdoğan shut down an opposition party).

While Carothers and O’Donohue focus on the contemporary world, historians who study polarization seek a broader perspective. In a previous article, I discussed the structural-demographic theory of Peter Turchin and Jack Goldstone, based on their statistical analysis of data from hundreds of historical societies. Turchin and Goldstone claim to have found a pattern: rising inequality typically leads to social instability. As people on the bottom rungs of the social ladder grow more miserable, they lose faith in the system and in the elites who run it.

Then, as social cohesion declines, a second and related dynamic, intra-elite competition, typically stokes more polarization. Over time, elites tend to skim off increasing amounts of wealth for themselves and their cronies, leaving less for everyone else and for society’s overall maintenance. As higher status yields tangible benefits, more people inevitably want to ascend the social ladder (in contemporary terms, they seek to become lawyers, politicians, CEOs, entrepreneurs, and investment managers). After a few decades, there come to be far more elite aspirants than elite positions available. Elite wannabes then divide into factions. Once that happens, defeating an opposing faction may become a higher priority for those at the top than actually trying to solve society’s problems.

When elites gain more from fighting one another than from solving society’s problems, those problems tend to get bigger and more numerous. And so, elite factions have more and bigger problems to blame on their rivals. The society as a whole has entered a self-reinforcing feedback loop of political-social polarization and disintegration.

In his book Why We’re Polarized, Ezra Klein describes this endgame in terms of contemporary American politics:

We are so locked into our political identities that there is virtually no candidate, no information, no condition that can force us to change our minds. We will justify almost anything or anyone so long as it helps our side, and the result is a politics devoid of guardrails, standards, persuasion, or accountability.”

The Polarized States of America

While polarization is occurring less in some countries than others, it is on full display in the United States. Many analysts and authors have tried to understand why.

Ezra Klein, in Why We’re Polarized, tells the story of the two U.S. political parties over the last few decades. In the 1950s, less ideological difference separated the parties: there were liberal as well as conservative Republicans, and conservative as well as liberal Democrats. Compromise had to be achieved both within and between parties. Many political theorists saw this as a dilemma: both parties had essentially the same agenda, so voters had little real choice. Barry Goldwater’s conservative Republican candidacy in 1964 promised voters “a choice, not an echo.” Richard Nixon’s “Southern Strategy” in 1970 succeeded in convincing White conservatives in the old Confederacy to abandon the Democratic Party and become Republicans. Since then, the Republican Party has continued to swing further to the right, while the Democratic party has veered leftward on social issues. Republicans became overwhelmingly White and more likely to be rural and Christian; Democrats became a coalition of Blacks and Latinos with left-leaning (and often college-educated, upper-income, and non-Christian or secular) urban Whites. In fact, one of the greatest indicators of which party wins an area is its population density. The result: Americans now have a clear, even stark choice in the voting booth, but many Republicans and Democrats hate each other, and compromise is vanishingly rare.

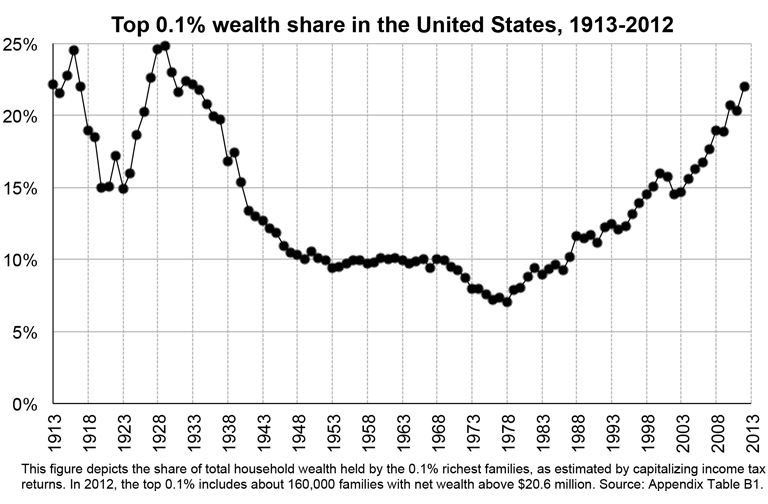

While Klein’s analysis is helpful, it fails to capture the bigger story of how polarization has waxed and waned in broad cycles throughout U.S. history. For this perspective, we turn to Peter Turchin’s Ages of Discord: A Structural-Demographic Analysis of American History. As noted above, Turchin’s theory holds that impoverishment of workers and elite infighting are the two main drivers of instability and polarization. He tests this theory by using indicators of general economic wellbeing and elite competition. Proxies for economic wellbeing include real wages, wages relative to GDP per capita, life expectancy, and average stature (since children raised with plenty of good food tend to grow taller). Proxies for elite dynamics include numbers of top wealth holders, numbers of law and business students, and polarization in Congressional voting patterns (using data and analysis from McCarty et al.). Turchin graphs the data over time and finds that declining wellbeing in the general population is clearly correlated with expanding ranks of elites on one hand and increasing political stress on the other.

Further, Turchin recounts the major political and economic events of American history in light of this correlation, and in the process makes both history and structural-demographic theory more understandable. Here’s a short summary.

In the aftermath of the American Revolutionary War came an “Era of Good Feeling”: more land was being forcibly taken from Native Americans, and so the average income and wealth of White Americans rose. This was the United States that Alexis de Tocqueville described glowingly in his 1835 book Democracy in America.

A trend reversal began in the 1820s during the Andrew Jackson administration: high rates of immigration gradually led to falling real wages for the common people, while cheap labor added to the fortunes of the elites. The overall economy depended on slavery and cotton production in the South, with the resulting wealth being invested in banks and industries in the North. The number of elite aspirants was growing quickly, resulting in more intra-elite conflict, which centered on the core issues of slavery and immigration. A growing split between Southern and Northern elites resulted in the Civil War, which halved the wealth of Southerners while enriching Northern bankers and industrialists.

Although the war freed African Americans from slavery, it failed to quell racism and other sources of division and enmity in the country. Elite competition and worsening wealth inequality continued through the Gilded Age, a period of persisting political violence. Elites feared a general revolution, such as the one that overwhelmed the Russian monarchy in 1917. In the decade before World War I, Republican president Theodore Roosevelt—with the cooperation of some wealthy industrialists—began a series of progressive reforms, which eventually included the initiation of the federal income tax (high earners were taxed at proportionally higher rates) and the outlawing of child labor. Immigration was significantly curtailed, and a more slowly growing labor pool tended to put upward pressure on wages. Nevertheless, political violence continued in the 1920s, with lynchings and deadly labor disputes. (Dan Barry, writing in The New York Times, notes the ways our 2024 political reality rhymes with that of 1924: “At play [in the ‘20s] were the tensions between the rural and the urban; the isolationist and the world-engaged; the America of white Protestant Christianity and the multiracial America of all faiths; the America that distrusted immigrants and the America that saw itself in those immigrants, and wished to extend a hand.” Meanwhile, a new communications medium—radio—was stoking ideological divisions. It all does sound eerily familiar.)

The Great Depression underscored the need for continued progressive reform. Franklin Roosevelt’s Democratic administration proposed laws and regulations that improved workplace conditions and increased wages; it also instituted Social Security and inheritance taxes. In the years from 1930 to 1970, inequality greatly abated and elite competition was checked; it was, in Turchin’s view, a “second Era of Good Feeling.” Times were hard, but Americans faced them with a sense of common purpose (though Blacks, Native Americans, and others were once again excluded from much “Good Feeling”).

Source: Saez, E. & Zucman, G. (2014). Wealth Inequality in the United States since 1913: Evidence from Capitalized Income Tax Data. https://doi.org/10.3386/w20625

World War II brought more shared sacrifice, and a further reduction of economic inequality. The U.S. entered the post-war period with relative national unity, international dominance, and plenty of individual opportunity. The shadow side of “Good Feeling” was mass conformity, consumerism, and paranoia. The 1950s introduced McCarthyism, but it also saw the beginnings of the civil rights movement and a widespread hope that all would eventually benefit from general prosperity.

The second great trend reversal in American history began in the 1980s. Republican-led tax cuts for the wealthy, along with increased immigration and loss of labor union membership, resulted in falling real wealth and income share for hourly wage earners. Meanwhile, the number of Americans seeking law degrees soared, as did the number of millionaires and, eventually, billionaires. The Republican Party had for decades represented the interests of the wealthy while the Democratic Party championed the cause of wage earners; but, under the Clinton administration in the 1990s, Democratic Party leadership began instead to court successful, educated urbanites, including entertainment and technology elites. Wage earners, with diminishing representation in government, lost ever more ground. Today, according to Turchin’s analysis, socio-political instability indicators are as strong as during the lead-up to the Civil War.

Into this maelstrom descended billionaire Donald Trump, announcing his presidential candidacy in 2015. As candidate and president, Trump reshaped the Republican Party as a personality cult, and, with his rhetoric of economic populism, has succeeded in attracting more Black, Latino, and union-member voters. He courted autocrats, including Vladimir Putin of Russia and Kim Jong Un of North Korea, and has recently hosted Hungary’s Viktor Orbán at his Florida resort. Upon losing his re-election bid in 2020, he incited an insurrection at the U.S. Capitol building and helped lead a “fake electors” scheme to overturn the election results. Trump encouraged his followers to think of Democrats as not just political rivals, but enemies and degenerate human beings. Meanwhile, Democrats viewed Trump as an aspiring dictator, and his supporters as cultic dupes.

The toll on U.S. democracy is hard to miss. In The Economist magazine’s annual Democracy Index, the United States is now listed as a “flawed democracy” and lags behind countries such as Malta, Spain, and Estonia. Americans agree: according to a recent Pew Research Center poll, 72 percent say the U.S. used to be a good example of democracy, but isn’t anymore.

Two paragraphs in a 2020 essay by Jack Goldstone and Peter Turchin sum up the political dilemma of the U.S. in the current decade so revealingly that they deserve to be quoted in full:

. . . American politics has fallen into a pattern that is characteristic of many developing countries, where one portion of the elite seeks to win support from the working classes not by sharing the wealth or by expanding public services and making sacrifices to increase the common good, but by persuading the working classes that they are beset by enemies who hate them (liberal elites, minorities, illegal immigrants) and want to take away what little they have. This pattern builds polarization and distrust and is strongly associated with civil conflict, violence and democratic decline.

At the same time, many liberal elites neglected or failed to remedy such problems as opiate addiction, declining social mobility, homelessness, urban decay, the collapse of unions and declining real wages, instead promising that globalization, environmental regulations and advocacy for neglected minorities would bring sufficient benefits. They thus contributed to growing distrust of government and ‘experts,’ who were increasingly seen as corrupt or useless, thus perpetuating a cycle of deepening government dysfunction.

In short, the United States is now disunited to a greater degree than at any time in living memory. We are two Americas nearly at war with each other. Political scientists speculate whether the country’s current extreme polarization could provoke an actual civil war, as in the 1860s (a recent movie based its plot on such a scenario). The more likely outcome, according to some historians, is “civil war lite”—a general increase in political violence similar to Italy’s “Years of Lead” (a roughly 15-year period starting in 1969, when extreme left and right militias perpetrated a explore series of bombings and assassinations). Virtually all informed observers say that extreme polarization in America is unlikely to end soon, or entirely peacefully. Peter Turchin foresees U.S. instability continuing for decades.

A further political decline of the U.S. would inevitably have international implications, with impacts on other democracies and alliance partners. Also, the foundering of America’s democratic institutions would likely make it harder for the nation to act coherently and consistently to address cascading problems such as climate change.

Reversing Extreme Polarization

Is there anything that can be done to overcome polarizing trends in the United States and elsewhere? Here are some recommendations from sociologists, political scientists, and historians.

In the U.S., institutional reforms could help defuse partisan animosity. Ezra Klein suggests “bombproofing” the government against political disaster, citing several possible institutional changes (which, unfortunately, sound a bit like a liberal’s wish list), including:

- Get rid of the “debt ceiling,” the law requiring Congress to approve limits to government borrowing. Negotiations over the debt ceiling—which has no real usefulness—have, in recent years, turned into partisan standoffs risking the fiscal soundness of the government.

- Do away with the electoral college. This could be accomplished without need for a constitutional amendment via the National Interstate Popular Vote Compact.

- Reform the House of Representatives by creating combined multi-member districts with ranked-choice voting (this would in effect get rid of gerrymandering). Also, abolish the filibuster.

- Give Washington, DC, and Puerto Rico congressional representation.

- Rebuild the Supreme Court by giving it fifteen justices: “each party gets to appoint five, and then the ten partisan judges must unanimously appoint the remaining five.”

- Make voting easier, such as by implementing national automatic voter registration.

Rachel Kleinfeld and Aaron Sobel, writing in USA Today, offer a recipe for personal action to defuse political polarization:

- Call out your party.

- Avoid bad jokes.

- Make social media kinder.

- Downplay the fringes and highlight the median.

- Emphasize disagreement within parties.

- Act with empathy and help others behave empathetically as well.

- Avoid repeating misinformation, even to debunk it.

Peter Turchin, in his recommendations for reversing polarization, focuses on the slowly developing trends he’s identified that undermine social stability. In his book End Times: Elites, Counter-Elites, and the Path of Political Disintegration, he points to societies that rescued themselves from civil peril. One example: during the Chartist period (1819-1867), England faced a crisis of extreme inequality and deadly popular protest. Reforms were instituted, including repeal of the Corn Laws (which imposed tariffs on imported grain) and the granting of the right for workers to unionize. Workers also benefitted from a population safety valve provided by England’s far-flung empire: millions of Britons emigrated to nations like Canada and Australia, thereby decreasing the British domestic labor supply and raising wages. As a result of these actions and circumstances, revolution was averted.

In the current U.S. situation, Turchin believes the “wealth pump” that funnels money away from workers and toward elites must be shut down if breakup of the nation is to be avoided. That requires driving wages up. However, it would not be an immediate cure:

“Shutting down the pump reduces elite incomes, but does not reduce [elite] numbers. This is a recipe for converting a massive number of elites into counter-elites, which will most likely make the internal war even bloodier and more intense. However, after a painful and violent decade, the system will rapidly achieve equilibrium.”

In End Times, Turchin doesn’t discuss in detail how to stop the wealth pump. Some of the possible ways (tax the rich at higher rates once again, break up large corporations, and provide more services such as universal health care) are championed by liberals such as Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren; other ways (restrict immigration and imports so as to drive up wages) are core Trump economic policies. All are controversial and would take time to have much effect on polarization.

Further, most of these reforms (including institutional ones, like doing away with the filibuster, and economic ones, like taxing the rich at higher rates) would require, if not consensus, at least coherent majoritarian action by Congress—which, these days, is difficult even to imagine. Nevertheless, political organizing could build constituencies to support such ambitious reforms.

Other than voicing support for institutional and economic reforms, what can individuals, households, and communities do to defuse the polarization bomb? An obvious remedy is to find ways to engage with one another across party lines. Some volunteer-led organizations (the largest of which is Braver Angels) encourage their members to reach out to neighbors with differing political beliefs and explore what they have in common.

Psychologist Peter T. Coleman, in The Way Out: How to Overcome Toxic Polarization, observes that people who embark on this kind of bridging and dialog work are often initially undertrained and unprepared, and may end up failing to connect with those with whom they disagree. Coleman’s book, which is based on years of research, is a training manual for serious depolarizers, and assumes readers care enough to devote significant time and effort toward examining their own assumptions and theories of change, and toward building long-term associations with people in their communities who may initially regard them with suspicion.

What about polarization outside the U.S.? Each country has a unique trajectory in terms of its history, economy, and institutions. Carothers and O’Donohue, along with their coauthors, examine in detail nine countries experiencing significant polarization. In some cases (e.g., Turkey), defusing bitter partisanship is difficult because polarization serves the interests of an authoritarian ruling party. For each country, the authors’ advice boils down to essentially the same recipe of dialog and bridging efforts, institutional reform, political party reform, and media reform, tailored toward specific national circumstances. If all else fails and a country is descending into chaos and bloodshed, international intervention may be the only answer.

Recent research has found that, despite increasingly politically polarized views about climate change in many countries, people across the political spectrum were willing to engage in the climate-mitigating action of planting trees. And the conservatives who took part in tree planting were then more likely to support climate policy efforts. This suggests we should spend less time trying to convince one another to change opinions that have already been shaped and solidified by political party rhetoric, and more time engaging our communities in participatory projects that improve environmental and social conditions. Political deadlock on climate change can also be broken by citizen assemblies, with members chosen at random and tasked with making recommendations for local climate action.

In his book Tribe: On Homecoming and Belonging, Sebastian Junger cites overwhelming evidence that we humans have an evolved instinct to live in small, cohesive groups, and that conflict with an opposing group tends to make our own group cohere more fiercely (an observation epitomized in the title of another book, War Is a Force that Gives Us Meaning, by Chris Hedges). Can our species evolve past its entrenched ingroup-outgroup social dynamics? In Belonging without Othering: How We Save Ourselves and the World, john a. powell and Stephen Menendian say that it can and must. They propose that humanity adopt a paradigm of belonging that does not require an “other” to fight against. This would require building institutions that are participatory and non-hierarchical and adopting personal attitudes and practices that orient society toward a future of mutual respect, cooperation, and healing.

We live in turbulent times. There are three likely responses: choose sides and join the melee, try simply to survive tumult without adding to it, or attempt to resolve turmoil by making peace. The last of these is the hardest. Getting past polarization will require many more of us to take that road less traveled.

* * *

This essay is part of a series of interviews, articles, and events that Post Carbon Institute is hosting on the topic of political polarization in advance of contentious elections in the United States and elsewhere. Sign up for the Surviving Political Polarization Deep Dive to join a webinar on October 8 featuring Professor Lilliana Mason, author of Radical American Partisanship: Mapping Violent Hostility, Its Causes, and the Consequences for Democracy and Cecelie Surasky from the Othering & Belonging Institute, and to watch recorded interviews with Jennifer McCoy and Nichole Argo exploring concrete ideas and models for overcoming political polarization in our communities.

Image credits: Protests at George Washington University: Ted Eytan, CC BY-SA 2.0.

![[Power book cover]](https://richardheinberg.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/cover_POWERcatalog-proof_300x450.jpg)