MuseLetter #238 / March 2012 by Richard Heinberg

Download printable PDF version here (PDF, 123 KB)

This month’s Museletter comprises three short pieces on the topic of energy. First is an update on China’s devastating coal consumption; the following two concentrate on the current headline energy issues in the US – Keystone XL, and gas prices.

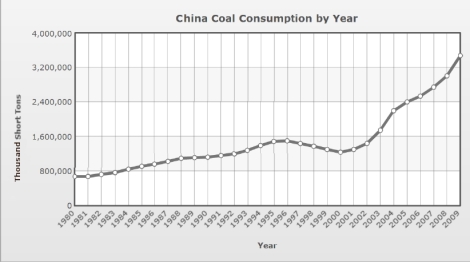

China Coal Update

World coal production and consumption data for 2011 are not yet compiled and published, but one key number is in. China’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology reports that the country’s coal output rose 8.7 percent from 2010 to reach 3.88 billion short tons last year. For comparison, US consumption in 2010 was just over 1 billion tons—and holding steady (mostly due to cheap natural gas prices). If the current trend continues, China will burn well over 4 billion tons of coal in 2012, four times as much as the US.

World coal production and consumption data for 2011 are not yet compiled and published, but one key number is in. China’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology reports that the country’s coal output rose 8.7 percent from 2010 to reach 3.88 billion short tons last year. For comparison, US consumption in 2010 was just over 1 billion tons—and holding steady (mostly due to cheap natural gas prices). If the current trend continues, China will burn well over 4 billion tons of coal in 2012, four times as much as the US.Asia-Pacific coal consumption dwarfed that of the rest of the world last year, accounting for about 70 percent of total world coal consumption, assuming a continuation of the 9.1 percent growth seen from 2009 to 2010. Asia-Pacific coal output has doubled, and doubled again (a 400 percent increase) since 1980.

China alone is now responsible for just about half of the world’s coal consumption, which amounts to nearly 8 billion short tons.

Chinese greenhouse gas emissions totaled 8.24 billion metric tonnes of CO2 equivalents in 2010; the 2011 figure will likely clock in at over 8.8 billion tonnes. The US racked up 5.5 billion metric tonnes of emissions in 2010, out of a world total of 33.5 billion tonnes.

The US still ranks first in terms of per capita emissions among the big economies, with 18 metric tonnes emitted per person; China emits under 6 tonnes per person, while the world average stands at 4.49 tonnes per person.

Two questions beg discussion:

First, when and how will China’s coal consumption stop growing? Given that current consumption rates are off the charts when compared to forecasts being issued just a few years ago, and that production problems (due to increasing mine depths and transport bottlenecks) are becoming more common, will consumption hit a sharp peak and decline rapidly—perhaps within the next few years? The country is reorganizing its mining industry and building new rail lines; over the short term, this could alleviate some of the supply pressures that caused Beijing to become a net coal importer in 2009. However, exponential rates of growth never continue for long on this finite planet of ours. At seven percent annual growth, China’s coal output would double every 10 years; is even one more doubling even remotely possible? What will be the economic consequences for China when production finally does top out?

Second, can the world save itself from a climate apocalypse unless China leads the way? Talk of “climate justice” (which emphasizes the higher per-capita emissions of wealthy nations) is all well and good, but the harsh reality is that even drastic emissions cuts by the US will mean relatively little unless China also cuts soon and fast. So far, indications are that Beijing is keeping the carbon pedal to the metal, despite concurrent efforts to become a world leader in renewable energy. Barring a dramatic global emissions policy breakthrough, resource limits and economic contraction seem to offer the main hope for keeping climate change to merely “catastrophic” levels.

Source EIA

Pipe Dreams

The ongoing controversy over whether to green-light the building of the Keystone XL pipeline to connect Canada’s tar sands with refiners on the Gulf coast is often framed in terms of whether the jobs it will create justify the environmental risks. Let’s ignore those risks for the moment. Forget climate change. Forget leaks. Forget potential damage to streams and aquifers. Now does the pipeline make sense?

Not much.

First, the jobs: just how many are we talking about? Probably the most authoritative source of data in this regard is the Final Environmental Impact Statement for Keystone XL from the State Department, which tells us that building the pipeline and pump stations “would result in hiring approximately 5,000 to 6,000 workers over the three year construction period.” But after that, only 20 permanent employees would be needed to operate Keystone XL. Indeed, a Cornell University study has concluded that the project would kill more jobs than it created, partly as a result of higher oil prices. So the jobs argument is a red herring—especially in light of the news that roughly three times more jobs are created in the renewable energy industry than in the fossil fuel industry per dollar spent (according to research at the PERI Institute at UMASS Amherst).

Profit is the understandable industry objective here, not jobs. More specifically, industry insiders acknowledge one goal of Keystone XL has been to remove a glut of unrefined petroleum accumulating in Cushing, Oklahoma at the terminus of the current Midwest pipeline system. Because of that glut, US oil prices have for the past few years lingered around $15 per barrel lower than the international price. Bottom line: the industry wants Americans to pay more for oil. So why should we want the pipeline, if that’s the case? (Breaking news: on February 28 TransCanada informed the US State Department that what had been the Cushing-to-US Gulf Coast portion of Keystone XL will be constructed as a stand-alone Gulf Coast Project, not requiring a Presidential Permit process. Looks like this industry problem is solved regardless what Obama ultimately decides.)

Now comes the geopolitical argument: Keystone XL offers the promise of a secure supply of oil. We’d rather import crude from Canada than Venezuela or the Middle East.

Granted, Canadians are likely to remain dependable business partners for the foreseeable future. But tar sands oil is not the same as conventional petroleum. And this difference has practical, economic implications that trump geopolitics.

When energy analysts measure and compare the qualities of differing energy sources, one of their key criteria is the ratio between the amount of energy invested in production and the amount of energy produced. For conventional oil, that ratio used to be in the range of 100 to 1—a spectacular energy profit that helped fuel the industrial boom of the 20th century. As the petroleum industry has chewed through the low-hanging fruit of easily accessed oil, that ratio has gradually fallen. With tar sands, the energy return on energy invested is an abysmal 5 to 1, according to analysis by Herweyer and Gupta. (For reference: anything below about 10 to 1 puts us back into the pre-industrial energy profit range.) Tar sands producers make money largely because they are using cheap natural gas as an energy input with which to make higher-priced syncrude. While the financials work as long as oil prices remain high, from an energy security standpoint the exercise makes little sense. If all our energy sources had such a dismal return on energy investment we’d be producing much of our energy just to fuel the next increment of energy production; we’d have little left over to power cars, planes, and tractors.

Because the easy oil is gone and prices are high, lower-grade resources (like tar sands) that were previously uneconomic are now profitable. Accountants who know nothing about energy analysis tell us this is a good thing because the quantity of low-grade fossil fuel resources is so immense. But as these make up a larger part of our energy mix, the overall quality of our energy declines.

Jobs don’t justify the Keystone XL pipeline. It will raise fuel prices for Americans. And it further locks us into a future of declining energy quality and increasing cost.

So, even ignoring environmental risks, the argument for the pipeline falls flat. But we cannot afford to ignore those risks, as they imply real and enduring costs.

As long as we delude ourselves that replacing depleting easy oil with expensive, low-quality bitumen is good energy policy, we succeed only in delaying the necessary transition to a viable future of energy conservation and renewables. Wouldn’t it be a wiser move from a cost, jobs, environmental, and energy security perspective to invest our money in needing less oil?

$5 Gas = Long, Hot, Crazy Summer

Here in northern California gasoline is now retailing for $4.20 a gallon. Prices haven’t been this high since mid-2008. Forecasts for $5 per gallon gas in the US this summer are now commonplace. What’s driving prices up?

Most analysts focus mostly on two factors: worries about Iran and increased demand from a perceived global economic recovery. However, as we will see, there are also often-overlooked systemic factors in the oil industry that almost guarantee us less-affordable oil.

Iranian Poker

Iran wants nuclear power and (probably) the capacity to build a nuclear weapon; the latter is unacceptable to Israel and the US. But there is more to the standoff than this. Iran is a strategic oil and gas exporting country that, for the past 30 years, has escaped integration into the US system of client states; it also occasionally provides assistance to Israel’s enemies. Following the disastrous US invasions and occupations of Iraq and Afghanistan, Iran has emerged as the principal power in the region, capable of further destabilizing either of its war-torn neighbors. And Tehran has led a move to ditch the US dollar as the standard currency of exchange in the global oil market.

Western sanctions include oil export embargoes that will gradually tighten over the coming months. Tehran has turned the threat around by proactively cutting off supplies to France and the UK. If the situation spins out of control in any of several possible directions, oil prices could shoot to $200 a barrel. So worry alone is keeping prices up.

Of course, the downside of open hostilities could include much more than unbearable oil prices. Nearly the entire Middle East could be thrown into chaos for the foreseeable future. It’s even conceivable that Russia and/or China could be drawn into the conflict in some way.

Hungry Chinese Hordes in Buicks

Meanwhile oil prices are also tied to shifting assessments of the state of the global economy. On days when the financial news is good, oil prices nudge up; on days when the luster on the latest Greek bailout package fades, oil prices tumble. The ongoing Greek debt crisis promises to plunge the EU into recession this year; on the other hand, the Dow Jones average is flirting with 13000.

If the world economy consisted only of the US and the EU, oil prices would probably be trending substantially lower than they are. But China increasingly commands attention. There, oil consumption is still soaring (it grew 6 percent in 2010 and again in 2011), and the Chinese are better able to withstand high prices because they wring more economic utility from every precious drop. The situation must be puzzling for many Americans. With gasoline consumption in the United States at a five-year low and domestic oil production at a six-year high, it seems incomprehensible that prices would be staging a rally. Americans have to get used to the idea that the US is no longer at the center of the universe.

Then there are oil supply disruptions in South Sudan, Syria, and Yemen. And of course those pesky oil-futures speculators, who pile on to magnify trends on both the upside and the downside.

Yet these are all short-term factors; there are also slower-acting forces pushing up petroleum prices. And it is these that we really should be paying attention to, because they will be with us for years to come and are generally very poorly understood.

The Peak of Peak-Oil Denial

Costs of production are rising inexorably—and fairly rapidly—as a result of replacement of conventional crude with oil produced from horizontal drilling and hydro-fracturing, ultra deepwater drilling, and tar sands. Only a decade ago, a world oil price of $20 per barrel evidently provided plenty of incentive for the industry to develop new supply sources, as total global production continued to increase year after year. Today, most new projects look uneconomic if oil prices are anything shy of $85. Ironically, pundits often depict this shift as a miraculous new development that promises oil aplenty till kingdom come.

During the past few months, op-eds and talking heads have announced the death of “the peak oil theory” even as actual world crude production rates remain stagnant and oil prices soar. The fallacy in this thinking arises from a confusion of reserves with production rates. With oil prices so high, staggering quantities of low-grade hydrocarbons become theoretically profitable to produce. It is assumed, therefore, that the scarcity problem has been solved. If we extract enough of these low-grade resources, that will bring oil prices down! But of course, if the oil price goes down then these unconventional sources become uneconomic once again and effectively cease to be countable as reserves.

The absurdity of the “new golden age of oil” line of thinking will take a while to reveal itself; how it will do so is fairly easy to divine from trends in the “fracking” shale gas industry, where temporary abundance (due to high rates of drilling a few years ago when gas prices were high) has driven gas prices back down to the point where producers are losing money, cutting drilling rates, and selling off leases. All that’s left to this sad story is the coming denouement, wherein shale gas producers go bankrupt, production rates fall, and the nation finds itself back in the midst of a natural gas supply crisis that pundits claimed had been deferred for a century.

The oil problem can be summed up simply: Fossil fuel supply boosters know how to add, but they’ve forgotten how to subtract. Seeing new production coming on line from North Dakota, for example, they extrapolate this growth trend far into the future and forecast oil independence for the nation. But most US oilfields are seeing declining rates of production, and individual wells in North Dakota have especially rapid decline rates (up to 90 percent in the first year). Do the subtraction properly, and it’s plain that net supplies will continue growing only if drilling rates climb exponentially. That, again, spells higher production costs and higher oil prices. If the economy cannot support higher prices, and hence high drilling rates, then net total rates of production will drop. The one future that is impossible to achieve in any realistic scenario—low prices and high production rates—is precisely what is being promised by politicians and oil industry PR hacks.

Oil and Politics: Together Again

What will happen later this year if gas prices do break the $5 per gallon psychological barrier?

First, the problem is likely to directly impact the US far worse than most other nations. Countries that tax fuel at high rates (including most European nations) have in effect already adapted to higher prices and will therefore be somewhat cushioned from the impact. Meanwhile countries that export oil will actually benefit from expensive crude.

Some analysts have suggested that price run-ups of the past few years have forced the US to adapt, and that America is now more resilient to oil price shocks than was formerly the case. Our new cars are more fuel efficient, and most industries (including the airlines) have by now factored higher oil prices into their business models. There is some truth to this, but the adaptation is only partial at best. When gas hits $5 a gallon, consumers will need to cut back somewhere. They’re already in debt up to their eyeballs and facing stagnant or declining household incomes. Something has to give.

Let’s not forget (though we wish we could): it’s election season! Republicans are already hammering Obama over the prospect of $5 gas and promising that, if elected, they will drive prices down to half that level. Meanwhile, with the exception of Ron Paul, they’re demanding harsher dealings with Iran, and are thus exacerbating one of the primary factors driving prices up. Altogether, it’s a neat trick.

Obama will be doing everything he can to keep gasoline prices in check. But what are his options? He could open up the sale of drilling rights on more federal lands—yet while that might make the fossil fuel industry happy, it will have no immediate impact on oil markets.

The one thing he could do that would have some short-term effect is to sell oil from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR) on the open market. The day of the announcement, oil prices would plummet. They might remain depressed $10 or more for a few weeks, but the impact would only be temporary. Meanwhile Obama’s Republican rivals would decry the use of the SPR for political purposes. Opening the SPR would in any case offer no solution to the deeper problems making fuel less affordable. And an emptying of the SPR prior to a potential showdown with Iran over the Strait of Hormuz would indeed be foolish.

In fact, the only thing likely to reduce prices substantially and for a long period of time is serious, prolonged global economic contraction. But this is unlikely to be a plank in any candidate’s platform.

Lots of smart people will be striving to manage these worsening problems. Obama will try to keep a lid on the Israel-Iran dispute until after the election. He’ll aim to keep gas prices down while appearing to give every possible perk to the oil and gas industry. He’ll also try to keep impacts to the economy minimal—or at least delay the release of statistics that reveal just how bad the situation really is.

At the same time, though, his political enemies will be highlighting economic damage and trying to exacerbate the geopolitical crisis.

Keeping this simmering pot from boiling over may just be more than mere mortals can do.

![[Power book cover]](https://richardheinberg.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/cover_POWERcatalog-proof_300x450.jpg)